The transformation of Central Asia under Soviet power

There existed three Khanates before the Russian conquest, namely, Bukhara, Khiva and Kokand.

There existed three Khanates before the Russian conquest, namely, Bukhara, Khiva and Kokand.

(In the Central Asia of the 19th century, half of the area covered by present-day Turkmenistan, the whole of modern Uzbekistan, almost the whole of present-day Kirghizistan and the southern region of what is now Kazakhstan were occupied by the khanates of Khiva, Bukhara and Kokand).

Timeline:

| June 1865 | Tashkent captured by General Charnayev |

| August 1866 | Tashkent declared part of Russia |

| 1867 | Governor-Generalship of Turkestan established with its headquarters in Tashkent and General K P Kaufman appointed as the first Governor-General |

| April 1868 | General Kaufman storms Samarkand and imposes a Treaty on Bukhara which reduced the Khanate to the status of a vassal |

| 1873 | Khiva overrun and its Khan forced to acknowledge that he was "the humble servant of the Emperor of all Russians" and to renounce "all direct and friendly relations existing with neighbouring rulers and khans". |

The subjugation of Khiva marked a new era in the history of Russian advance. The last semblance of organised resistance to the Russian onslaught disappeared and the tsar found himself the undisputed suzerain of the great Khanates.

While Turkestan was a tsarist colony, Khiva and Bukhara were only nominally independent but actually "something like colonies" (Lenin, ‘Speech on the attitude towards the provisional government’ at First All-Russia Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, June 1917, CW Vol.25 p.27).

In 1916 the population of Russian Turkestan was 7.4 million, that of Bukhara 2,236,000 and of Khiva 640,000.

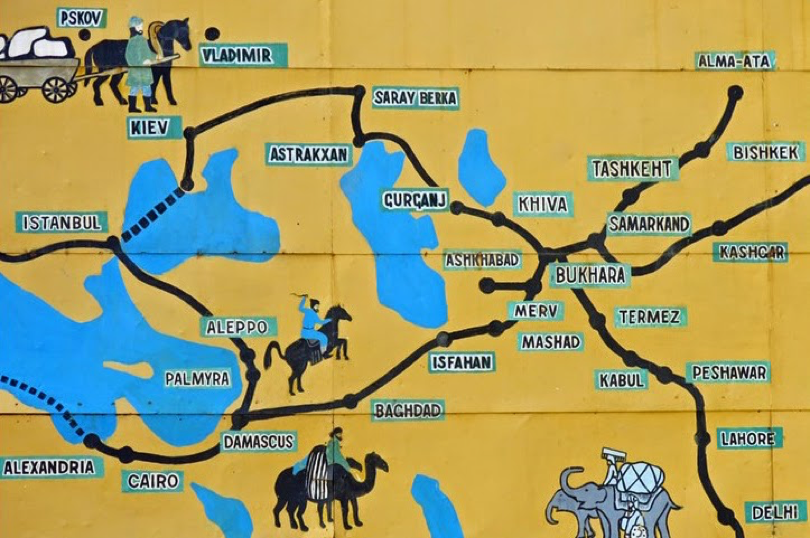

After the conquest Central Asia became a region for the export of raw materials, and Russia built 3,377 km of railways, with 14 repair workshops, to serve the raw material processing industry.

The introduction of railways marked the beginning of the end of economic seclusion of different regions inside Central Asia and also the end of isolation of the whole of Central Asia.

In Central Asia, numerically the industrial proletariat was very weak before the revolution. Even among the Uzbeks, where it was more numerous compared to its size among other peoples of Central Asia, it constituted an insignificant part of the entire population. There were:

12,702 Uzbek industrial workers

1,144 in Kazakhstan

242 Turkmen workers, and

206 Tajik workers.

The Central Asian economy before the revolution was characterised predominantly by feudal relations of production and autocratic rule – with a few shoots of capitalist development sprouting among it – the rise of new towns, railway construction, emergence of capitalist agriculture, light industries and intellectual awakening.

Health and education facilities were almost non-existent.

There were only 212 doctors, entirely confined to cities, in Turkestan, leaving people at the mercy of charlatans and quacks for treatment in case of illness.

In Turkestan in 1914-15 there were 335 state educational institutions attended by 31,492 students, but in 1899 there had been 11,964 mosques with 11,860 mullahs – with more than 8,000 receiving religious education in various types of religious school.

In Bukhara and Khiva, the situation was even worse. In 1920, there were 3,000 mosques and 877 madrassas in Khiva. The army of mullahs in Bukhara numbered 40,000.

Literacy was confined to a handful of khans, bais and mullahs and a very few peasants. Literacy among women was as good as absent.

The Kirghiz, Krakalpaks and Turkmens did not even have their own written language.

Literacy stood at 2% among the Uzbeks, 0.7% among the Turkmens, 0.5% among the Tajiks and 0.2% among the Kirghiz and Kalpaks.

The uprising of 1916 and its significance

The occasion for the uprising of 1916 was the Decree of 25 June 1916 concerning the mobilisation of the local population for work behind the front. In spite of the failure of the uprising, through cruel suppression, it played a significant role in the history of colonial peoples.

It turned from an anti-colonial into an anti-feudal movement. Beginning with spontaneous demonstrations against mobilisation, it grew into armed struggle. It did not aim at secession from Russia, but only at freedom from national-colonial oppression.

The mobilised workers and dehkans (poor peasants) who lived and worked in Russia became politically active under the influence of Russian Bolsheviks and on their return to Turkestan became the vanguard of the native masses in the period between the February and October revolutions when they took a leading role in organising the Soviets of toiling Muslims.

The uprising of 1916 taught the Central Asian people a great lesson. It convinced them that only with the help and guidance of the Russian proletariat, and only through socialist revolution, could they liberate themselves from national and colonial oppression, and the bourgeois intelligentsia, which up this point in time had been siding with, and acting as flunkeys of, tsarist imperialism, also opened their eyes.

Contact between the masses of Central Asia and the ‘two Russias’ – that of the oppressed and that of the exploiters, the Romanovs and Stolypins oppressing and exploiting both the native Asians and the Russian peoples – and the Russia of revolutionaries fighting against social and national oppression, not only Russian kulaks and traders but also Russian peasants and industrial workers, scientists, teachers, workers and revolutionaries, opened the eyes of the Central Asian masses and brought them closer to the democratic and revolutionary movement in Russia. And this drawing together of Central Asian toilers with the Great Russian people became all the more significant as Russia became the centre of the world revolutionary movement as the Russian working class, having formed its militant revolutionary party, became the vanguard of the international revolutionary movement. The rising tide of the revolution in Russia could not fail greatly to influence Central Asia. The progressive forces in Central Asia gave a call for a joint struggle with the Russian proletariat against feudal and colonial oppression.

The Russian proletariat doubtless played a leading role in the socialist revolution in Central Asia. It roused the class consciousness of the native workers and in forging an alliance with the dehkans who were gradually attempting to extricate themselves from the clutches of the feudal exploiters and the clergy and who had, since the close of the 19th century, begun to enter the arena of political struggle, albeit spontaneously and in an unorganised manner.

From the beginning of the 20th century, an alliance began to form between tsarism and the native bais and mullahs against the rapidly emerging alliance of the Russian proletariat and the native workers and dehkans.

Starting from the years 1905-07, the process of alienation of the local masses from the national bourgeoisie was completed at the time of the 1916 uprising.

The victory of the February Revolution opened up new prospects for the national liberation movement in colonial Tajikstan, where people had by this time become convinced that they could achieve their liberation from national and colonial oppression and exploitation only with the help of the Russian proletariat. And they began to organise political activity, through the appearance on the stage of a number of class organisations – Soviets, committees and units of local working people.

Soviets of local toilers began to emerge towards the end of May and the beginning of June 1917. Organisationally the Russian proletariat also lent great assistance.

By the time of the October Revolution, the masses of Central Asia, consequent upon the growth of class contradictions, lost whatever little confidence they had in the reactionary organisations formed by native exploiters. Thus a revolutionary situation had fully developed and the crisis fully matured – leading to the outbreak of socialist revolution in Central Asia.

Establishment of Soviet power

In one of its first Decrees – the Decree on Peace – the Soviet government proclaimed the right of national self-determination as one of the basic principles of its foreign policy. It demanded the establishment of a just and democratic peace on the basis of equality of rights of all peoples and nations. It condemned all annexations of foreign land.

" In accordance with the sense of justice of democrats in general, and of the working class in particular, the government conceives the annexation or seizure of foreign lands to mean every incorporation of a small or weak nation into large or powerful state without the precisely, clearly, and voluntarily expressed consent and wish of that nation, irrespective of the time when such forcible incorporation took place, irrespective also of the degree of development or backwardness of the nation forcibly annexed to the given state, or forcibly retained within its borders, and irrespective, finally, of whether this nation is in Europe or in distant, overseas countries" (Lenin, ‘Report on Peace’ to the Second All-Russia Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ deputes, 8 November 1917, CW Vol.26, p.250).

The right to self-determination was also included in the Declaration of the Rights of the Working and Exploited People as a principle of national development in the Soviet state. It laid down the following principles as the basis of its national policy:

• Equality and sovereignty of the peoples of Russia

• Right of the peoples of Russia to self-determination up to secession and the establishment of independent states.

• Annulment of all national and religious privileges and restrictions.

• Free development of the national minorities and ethno-graphic groups inhabiting the territory of Russia. (Lenin, CW Vol.26 pp.14-15).

This Declaration became the basis for the setting up of the Soviet state on a federative basis "on the principle of a free union of free nations, as a federation of Soviet national republics".

These measures of the Soviet Republic pointed out to the oppressed peoples everywhere the true path to their liberation and roused their revolutionary consciousness.

The formation of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was the first step towards the founding of national states by the peoples of Central Asia; it was an event of world-historic importance.

The bourgeois nationalists came out openly against Soviet power towards the close of November 1917, convening in Kokand the so-called Regional Muslim Congress on 27 November and electing a Provisional Council of Turkestan consisting of 54 members, a third of whom were representatives of the Russian bourgeoisie.

The Kokand autonomy was not a national movement of Muslims against Russia as it was made out to be by some writers. It was in fact an expression of class struggle between the Muslim propertied classes in alliance with the Russian bourgeoisie and foreign imperialists, on the one hand, and the Russian proletariat supported by the Muslim working masses on the other. In other words, a struggle between the counter-revolutionary and revolutionary forces in Turkestan.

Owen Lattimore was correct when he summed up as follows: "As the revolution deepened from a political struggle into a class war, the lines of cleavage more and more grouped together the possessors, Russian and non-Russian, fighting to preserve at least something of the old order, and the dispossessed, Russian and non-Russian, trying to take complete possession of the new order" (Pivot of Asia, Little Brown, Boston, 1950, p.204).

The bourgeois nationalists had no coherent programme on the national question. Their alliance was a mixture of Pan-Islamists, who claimed all the Muslims of Russia to be a single nation and denied the existence of class differences among the Muslims, and Pan-Turkish who, representing the interests of the Tatar bourgeoisie, desired to established its class hegemony over all Muslims of Russia belonging to the Turkish linguistic group.

The Kokand ‘government’ launched on the night of January 30-31, 1918, an attack on Soviet power in Turkestan. Red Guards launched a counter-offensive on 19 February 1918 and by 22 February the Kokand ‘government’ was suppressed.

Khiva

Following the victory of the October Revolution, Khiva (currently a cultural gem in Uzbekistan) ceased to be a colony and its people were fully assured of the sympathy and support of the Soviet government for their struggle against the despotic rule of the Khan. Under the conditions of mass struggle arose the nucleus of the Communist Party of Khiva which began to organise and lead the people against the despotism of the Khan.

The Soviet government had, at the very outset, declared that it recognised the independence and sovereignty of Khiva under its Khan. But the reactionaries of Khiva, filled with blind hatred of Soviet power, crossed over to the imperialist camp and Khiva became an anti-Soviet counter-revolutionary centre in Central Asia, to where White Guards, Mensheviks, Social Revolutionaries, bourgeois nationalists and other counter-revolutionaries flocked. The Khiva counter-revolutionaries were in regular contact with the underground anti-Soviet organisation in Tashkent called the Turkestan Military Organisation, founded through the active participation of the American Consul, the French agent Castagne and the British Colonel Bailey.

After failing in his attempts to overwhelm Soviet territory, Junaid Khan (the Khivan despot) approached the Soviet government in April 1919 and sued for peace, resulting in the agreement of 19 April 1919 according to which Junaid Khan was not to indulge in any armed action against the RSFSR.

This agreement was, however, not observed by Khiva. Under the leadership of the Khivan communists, armed uprisings took place in a number of Khivan towns. The Soviet government, at the request of the people of Khiva, decided to aid the struggle against the White Guards. The Soviet army entered the territory of Khiva on 22 December 1919. On 2 February 2020, the Revolution in Khiva was victorious and the rule of the Khan was overthrown.

The First All Khwarezm Assembly of People’s Representatives met in April 1920 and declared the former Khanate of Khiva the Khwarezm Soviet People’s Republic.

Bukhara

Like Khiva, Bukhara (another Uzbek city of outstanding architectural beauty) was ruled by feudal despotism and was a protectorate of Tsarist Russia. The Muslim priesthood was extremely influential in Bukhara. Some 20,000 students studied in the maktabs and madrasahs. The Emir of Bukhara, in alliance with British imperialism, mobilising an army of 50,000 in August 1920 issued a fatwa for a holy war against the Bolsheviks. The Communist Party of Bukhara, formed in September 1918, in its programme called for the liquidation of the Emirate and its replacement with a People’s Republic.

At the invitation of the Communist Party of Bukhara, Soviet forces under Mikhail Frunze came to assist in the people’s liberation. After heavy fighting, Bukhara, the citadel of despotism, was taken by Soviet forces on 6 September 1920. On 5 October 1920, the First Kurultai (Congress of People’s Representatives) met in Bukhara and proclaimed a Soviet People’s Republic.

By the end of 1922, the main bands of counter-revolutionary basmachi had been defeated. From 1923 began the period of peaceful reconstruction in these republics. Much success was achieved in the work of organising trade unions, peasants’ unions and youth leagues. The popular masses were increasingly attracted to socialist development. The positive experience of socialist construction in adjacent Turkestan ASSR convinced the people in Khiva and Bukhara of the need to take the same path for their own republics also.

The complex process of Sovietisation and socialist reconstruction in Bukhara and Khwarezm and their economic development, as also the further development of Turkestan ASSR, was closely connected with the economic unification of the Soviet Republics in Central Asia. A decision was taken at an Economic Conference of the Soviet Asian Republics in Tashkent to coordinate economic activities of the three republics on the basis of a unified economic policy and a common economic plan. This decision facilitated the task of transition to socialism by Bukhara and Khwarezm.

But in both these republics their internal socio-political base alone was not sufficient for such a transformation. This transformation could not have been accomplished without close economic, cultural and political collaboration with the USSR, without the unity of the people of these republics with the working class and peasantry of the USSR, whose socialist industries and working class formed the necessary external base.

In October 1923, the Fourth All-Khwarezm Kurultai adopted a new constitution and proclaimed its transformation into a Soviet Socialist Republic.

In September 1924, the Fifth All Bukhara Kurultai proclaimed the Soviet Socialist Republic of Bukhara.

Their peculiar geographic location and historical context obviated for them the need to pass through a capitalist stage of social development. The alliance of their peasantry with the Russian proletariat made good the deficiency of the indigenous working class.

1924 witnessed national liberation carried out in Central Asia with the formation of:

• the Uzbek SSR and the Turkmen SSR (Union Republics which entered the USSR)

• Tajik – an autonomous republic within the Uzbek SSR

• Kazakh – areas became united in what was the called the Kirghiz autonomous SSR within the RSFSR.

This delimitation took into account the composition of the population, economic and ethnic distinctions, and geographical conditions.

"As a result of the national delimitation a number of nationally homogeneous states appeared in Central Asia in place of the former three multinational states. This helped in resolving the complex national tangle which considerably hindered the process of their socialist development. The old demarcation of political and administrative frontiers was solely a product of military, strategic and political exigencies of the time of Tsarist conquest. As such it only aggravated the national problem. The old frontiers cut across the ethnographic distribution of peoples of Central Asia and were utilised by the old regimes of Turkestan, Bukhara and Khiva to preserve their power by playing one national group against the other. The national delimitation changed the situation removing thus the very base of national antagonism on which bourgeois nationalists always sought to thrive" (Devendra Kaushik, Central Asia in Modern Times, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1970, p.212).

Socialist Industrialisation

The industrialisation drive in Central Asia started in 1926-27. The centre’s contribution formed a major part of the investment under the First Five-Year Plan, which was characterised by an impressive development of power production, machine building and metal industries. The Plan was successfully accomplished in the Central Asian Republics. The rate of industrial development during the Plan was faster there than in the central regions of Russia – 3.5 times as opposed to 2 times in the central regions.

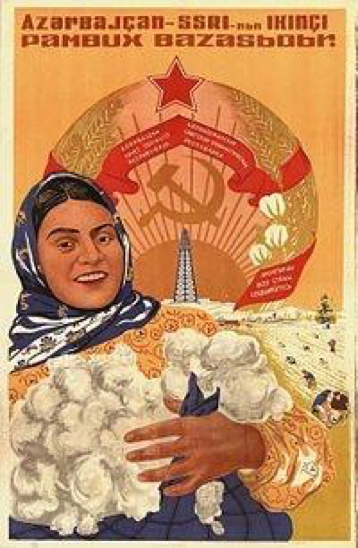

The Second Plan had the object of liquidating all exploiting classes and establishing socialism. At the end of it, industrial production in the USSR rose 8 times as compared to 1913 and 4.3 times as compared to 1929. By way of contrast, the average production of capitalist countries in 1937 was 102.5% of their production in 1929, and in 1938 had fallen to 90%.

With socialist industrialisation, the gap in the level of development of the central regions of Russia and Central Asia was to a very large extent equalised and on this basis the national question was satisfactorily solved.

While the increase in the value of industrial production for the whole of the USSR for the Second Plan period was 220.6% for the RSFSR, it was 243.0% for the Uzbek SSR and 355.7% for Tajikstan.

The capital investment rate was higher in Central Asia than in Russia.

The growth in the number of workers in big industries in Central Asian Republics was 59.5% in comparison to an increase of 22.2% in the central regions between 1932-37.

Over a period of just 3 decades, the relative share of cattle in agricultural power fell from 60-70% to almost zero in 1963, out of 13.5 m horse-power of energy in use in agriculture, only 200,000 horse-power was produced by draught animals.

In 1963, there were 130,000 tractors working on the fields in the Soviet Republics of Central Asia.

Industrial production in the USSR accounted for 80%, while agricultural production accounted for 20%. These ratios were not very different from those in central Asia.

By 1961, Soviet Central Asia, with a population of only 15m contributed 0.7% of the entire world’s industrial output, as compared to India which, with 19% of the global population, contributed only 1.2%.

Between 1913 and 1959 the gross industrial output of Uzbekistan increased 18 times, of Turkmenistan 21 times and Tajikstan 35 times.

"Between 1913 and 1959 gross industrial output in Uzbekistan increased 18 times, in Turkmenia 21 times, in Tajikstan 35 times and in Kirghizia 55 times. Central Asian industries now produced steel, rolled metal, non-ferrous metals, mineral fertilisers, metal-cutting lathes, cotton combines and tractors, excavators, oil and electrical engineering equipment, cotton, woollen and silk fabrics, footwear, clothes, tinned food, glass, cement, prefabricated ferro-concrete structures, etc. Central Asia now exports industrial goods not only to other Soviet republics but abroad as well. Automation and telemechanics are widely employed in its industrial enterprises, power stations and oil fields.

"In the meantime industry continues to develop apace. The industry of Soviet Uzbekistan has fulfilled the Seven Year Plan (1959-65) ahead of schedule. Today 69 countries of the world import Uzbek industrial goods – textile and agricultural machinery, chemical and mining equipment, excavators, compressor stations and electrical equipment" (ibid., pp. 230-231).

Transformation of agriculture

The basic problem of the Central Asian countryside was the question of transforming a technically backward, small and partially patriarchal and natural peasant economy into a large-scale mechanised collective socialist economy, bypassing the stage of large-scale capitalist farming based on the exploitation of farm labourers.

The socialist construction in the countryside of Central Asia went through three phases:

1. Preparing for transition to the socialist path (1920-29);

2. Mass collectivisation of agriculture (from the autumn of 1929 to the mid-1930s);

3. Consolidation and development of the collective-farm system (from the mid-1930s onwards).

In the preparatory period, land and water reform were carried out; irrigation facilities made available; peasants were supplied with modern implements and introduced to new agrotechnical methods, and supplied with easy credits by the state to make possible these improvements.

In the early 1920s the Soviet government distributed the private estates of the Russian tsar, the Khan and the Emir, big counter-revolutionary feudal landowners and the rich Russian settlers among the Central Asian peasantry. All the same, in comparison with Russia, agrarian reform proceeded slowly in Central Asia owing to the political backwardness of the peasantry. Only in 1925-27, when the Peasants’ Union Kishchi – the mass organisation of the poor and middle peasants – and the rural Soviets had gained in strength, when Party organisations had made their presence felt in the countryside, and the peasants’ consciousness had registered a rise, that a land and water reform was carried out and kulaks dispossessed of part of their land, making it possible to distribute 350,000 hectares of irrigated land among some 140,000 landless and poor peasants.

Be it noted that all these measures were carried out in the teeth of bitter opposition on the part of the kulaks, money-lenders and other rural leeches. Realising that the measures taken by the Soviet government were depriving them of their instruments of exploitation, they undertook a violent campaign against Soviet power, formed armed bands, murdered many a Soviet functionary and village activist. This intensification of class struggle only served to broaden the peasants’ political activity. The working peasant also rallied to the support of the Soviet government.

The peasantry of Asia was shown the way to gradual cooperative life through rural cooperatives – from the simplest consumers’ cooperatives, through credit and marketing cooperatives to the higher form of producers’ cooperatives, viz., the collective farms. The urban proletariat of the USSR provided great assistance to the peasants in the matter of collectivisation. At the height of collectivisation, large numbers of workers with adequate organisational and political experience, not to say technical and other expertise, were directed by the Soviet authorities to the countryside to help the peasantry. Industrial enterprises in Leningrad, Moscow and other industrial centres took various rural areas under their patronage, signed socialist emulation agreements with the peasants and floated funds to help the newly-organised collective farms with agricultural machines, etc.

Mass collectivisation met with fierce resistance by the hostile classes, who went around persuading the peasants to boycott collectivisation, to slaughter their cattle and flee, resulting in the destruction of a vast number of animals. Armed counter-revolutionary bands stepped up their activity, raiding peaceful villages in an effort to terrorise the peasants. However, all this was to no avail as the mass of the peasantry supported the drive to collectivise agriculture as the only means to prosperity and a cultured life.

The second half of 1929 marked the beginning of a mass movement for collectivisation in Central Asia, as indeed in the rest of the Soviet Union. After some initial hiccups and distortion by local officials of the Party’s line on collectivisation was put right, through directives from the centre and the reorganisation of Party and Soviet work in the villages, the founding of Party units in state farms, collective farms and machine-and-tractor stations, there was a dramatic increase in the size and scope of the collectivisation movement, in which the machine-and-tractor stations played a crucial role. In 1931 there were 2,330 tractors working in these stations in Uzbekistan alone. By March 1931, nearly 48% of the peasants had joined the collectives; this number increased 56.7% by May 1931. By 1937, of all the peasant families, 95% had united in collective farms, which covered 99.4% of the entire land cultivated by peasants in Uzbekistan. The socialist form of production thus became the dominant form in the agriculture of Uzbekistan.

Great progress was accomplished in the mechanisation of agriculture during the first two Five-Year Plans. In Uzbekistan in 1937, there were 163 machine-and-tractor stations with 18,267 tractors, which served 94% of all collective farms by the end of the Second Plan. With these developments there was a tremendous increase in the productivity of labour and yield of cotton per hectare rose from 9.6 centners (480 kg) in 1925 to 16.1 centners (805 kg) in 1937.

Similarly, in the other republics of Central Asia, the collectivisation of agriculture had been completed by the end of the Second Five-Year Plan.

Consequent upon socialist industrialisation and collectivisation of agriculture, socialism became victorious in the whole of the USSR, including its Central Asian Republics, by the end of the Second Plan. This was of world-historic importance for the solution of the national question in the USSR. During a very brief period of two decades, the erstwhile oppressed and backward peoples of Central Asia, who joined the Soviet family of nations following the October Revolution, completely changed their socio-economic and cultural relations, thus achieving not merely formal legal equality but also real economic equality.

Before the Revolution Central Asia had about 1.5 million individual peasant farms with the most primitive ploughs. Lack of land, low yields and cruel exploitation doomed the overwhelming majority of the peasants to a life of grinding poverty and cultural backwardness. Collectivisation changed the face of rural life and helped dramatically to improve the living standards in the countryside, making poverty a thing of the past. Instead of the old dilapidated mud hovels, the farmers now lived in well-built modern houses, surrounded by public services and modern amenities. The collective farms were adorned with schools, clubs, dispensaries, maternity homes, nurseries, radio relay stations, electric street lighting – with many farms having their own stadiums and cinemas.

Collective farmers’ homes often possessed consumer durables, which would have been completely out of reach in the old pre-collectivisation days.

The Soviet government, on the basis of the growing might of Soviet industry, supplied the Central Asian collective farms with the latest agricultural machines. In Uzbekistan alone, the number of tractors increased from 23,600 in 1940 to 69,300 in 1959. By 1961, the number of tractors in Central Asia totalled 127,800. In addition a large number of combines, excavators, bulldozers, aeroplanes and helicopters were generously supplied to the collective and state farms by the powerful socialist industry of the Soviet Union.

A whole army of agronomists and veterinary doctors served Central Asia’s agriculture – 16,000 specialists with higher education and more than 22,000 specialists with secondary special education. Most of them were of local nationalities.

Cultural revolution

The tasks of the cultural revolution were inextricably linked with industrialisation and collectivisation as mass illiteracy and ignorance are a formidable hindrance to economic progress. This revolution in the cultural sphere implied the liquidation of illiteracy among adults, introduction of compulsory education for children, creation of a modern public health system, scientific and technological development, promotion of arts, creation of a national intelligentsia, emancipation of women and building of a new cultural life.

Mass literacy is the bedrock of culture, for a person unable to read and write is not capable of operating complex modern machinery or appraise socio-political developments. Hence the drive for adult literacy and for children’s education was crucial to the success of the cultural revolution – not an easy task in a thoroughly backward Central Asia where the percentage of literacy was under 2%.

For many centuries the broad masses in Central Asia had no access to knowledge. The literacy rate in tsarist Russia barely passed 28%, while among the Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Turkmenians and Kirghiz, it ranged from an abysmal 0.5% to 2%. Natives were forbidden to study in their own languages, with their access to schools strictly limited. No written language existed for dozens of nationalities and ethnic groups.

After the October Revolution, the Soviet government established a system of public education which provided for universal and free schooling for all children. The school was separated from the church, and all private schools were closed. The right to conduct instruction in the native language of the peoples was established for all nationalities. For the first time alphabets were developed for some ethnic groups where none had existed previously.

Schools and literacy courses for adults were set up. What is more, cultural advance in Central Asia became a veritable arena of class struggle, as the reactionary mullahs and bourgeois nationalists opposed tooth and nail all cultural advance and new Soviet schools, especially for the girls. Many a cultural worker fell victim to religious fanaticism.

The decisive stage in this revolution began in 1929-30. In just two years, more than a million people in Central Asia, mainly peasants, were taught to read.

The case of Turkmenia is illustrative of the education drive in Central Asia where in 1937 about half a million people were attending schools from a population slightly over 1.2 million.

The literacy rate in Turkmenia had already reached 77.7%, while in Kazakhstan it had reached 83.6% (see Leon Emin, Muslims in the USSR, Novosti Press Agency Publishing House, Moscow, 1986).

At the invitation of VOKS – the Soviet Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries – a British delegation visited the Soviet Union in 1951. Among other places, it visited Tashkent (Uzbekistan). One of its members, S M Manton FRS, an internationally renowned scientist, recorded her impressions in The Soviet Union Today, a book she published in 1952 (Lawrence and Wishart, London).

Writing about Uzbekistan, she noted that before Soviet rule, only 1.6% of the population were literate. And yet, a very high level of culture had been attained by its people in so short a period of time, thanks to the Soviet system.

Up to 1918, no general education existed in Uzbekistan; there was no higher or pre-school education, and no technical education.

By 1924, a new national state and government had been created which was the greatest event in the life of Uzbek people, laying the basis for a freedom and for a development of education, economy and culture never before experienced.

By 1924, the pre-Revolution schools were closed and 917 schools had been built and equipped and their teachers trained in the face of stiff opposition from the Islamic clergy, an opposition which resulted even in the murder of a distinguished Uzbek writer.

Expansion was rapid. The initial 75,000 schoolchildren had risen to 166,000 in 1929, with 2,710 schools in operation, and to 1.3 million children in 1950, served by 5,000 schools.

There was compulsory attendance of 7-year schools everywhere, and ten-year schools in larger towns.

Illiteracy, except among some older people, had disappeared.

In 70% of the schools and in the universities, the Uzbek language was spoken, while in the remaining 30% of the schools the teaching was in Russian.

People of all races and nationalities were educated together in a spirit of unbreakable friendship among nations, with no racial or national prejudice. And it was Uzbeks, not Russians, who occupied positions of authority.

Higher education

Ms Manton says that in 1918 Lenin issued an order for the creation of a Middle Asian State University of Turkestan, as the area was called – subsequently it was divided up ethnographically into the five republics of which Uzbekistan was the most important, though not the largest.

The universities at Tashkent and Samarkand played the greatest part in the development of the republic. In turn, they established 36 other institutes of higher education, 17 teacher-training establishments, as well as polytechnics, institutes of medicine, agriculture, law, economics, fine art, and the Academy of Sciences, with its affiliated research institutions by 1952 – no mean achievement in so short a time. "The standard of the education work carried out by these institutes is in no way inferior to that in other parts of the world" (p.74).

In 1950, the higher educational institutions catered for 32,000 students.

This progress continued in subsequent years. While not a single institution of higher learning existed in the whole of Central Asia before the revolution, by 1959-60 nearly 211,000 students were enrolled in higher education establishments, besides 176,000 studying in technical and other special schools.

Ms Manton presents this picture of the importance attached by the Soviet state to the development of dramatic and operatic arts in Central Asia as well as elsewhere in the USSR:

"Before the revolution Uzbekistan possessed no theatres, and the Islamic religion prevented artists from portraying the human form. By 1946 thirty-seven theatres and 564 cinemas were in operation, and in 1951 the people of Tashkent possessed seven major theatres, besides those owned by industries, which present full translations of the great plays of all nations, ballet and opera, as well as modern products of local writers. An advertisement for Othello caught our eyes as we drove about the town. All qualified actors draw their State-paid salary with no anxieties concerning their future, and a growing and enthusiastic demand for their work keeps the standard high. Little did I expect to find in this Central Asian town a performance of Madame Butterfly which had nothing to learn from anything which I have seen in England.

"Opera house

"The building of a new opera house in Tashkent was started in 1938, but interrupted by the war. Uzbekistan had thrown her whole weight into the war drive as her limbless men showed, but in 1943 when the German armies were thrown reeling back from Stalingrad, the building was resumed and completed by 1946. The Uzbeks did not wait for the end of the war to continue their masterpiece of modern architecture with its immense areas of hand carving and eastern designs. Theirs is the same spirit found among the Stalingraders, who have completed their theatre, circus, palaces of culture and teaching institutions before a sufficiency of flats and houses could liberate the many unfortunates who have lived up to the summer of 1951 in dug-outs and patched-up cellars. The same spirit seems to prevail among all races of the Soviet Union" (p.68).

The successes achieved in public education in the Thirties were reflected in the proliferation of newspapers, magazines and books in national languages.

In 1962:

• 4,138 different books were published, running into editions of 39 million copies.

• 261 journals and other periodicals with a circulation of 29.3 million were published in Central Asia

• Central Asia had 41 theatres, 29 museums, 6,801 large libraries, 4,809 cinemas and 6,000 different clubs, as well as 47 higher education institutions.

Emancipation of women added greatly to these developments in the cultural sphere, to which we devote the following few paragraphs:

Emancipation of women

One of the most significant achievements of the October Revolution was the emancipation of women throughout Russia. Equally, a remarkable feature of the cultural revolution in Central Asia in the wake of the establishment of Soviet power was the liberation of Central Asian women. In the very first months following the October Revolution, the Soviet government abrogated all the old laws that humiliated and demeaned women and that denied them equality of status with men. The feudal concept of treating women as inferior to men was particularly deep-rooted in Central Asia. Something more than the adoption of new laws was needed to effect the genuine emancipation of women.

For such emancipation it was necessary, first, to make women politically conscious and convince them that they were the equal of men in all spheres of public life; secondly, to overcome men’s age-old arrogant attitude towards women; and, thirdly, and most importantly, to draw women into social production and public life through the provision of facilities that made it possible to do so. Be it said to the credit of the Soviet authorities that they succeeded in this goal so remarkably that they made women in the capitalist world look upon Soviet women with envy.

Here is a brief summary of what Ms Manton recorded in her book with regard to women in Uzbekistan, who went to school for the first time following the October Revolution. In 1927-28 girls accounted for 26% of school children; by 1940-41, they accounted for 44%.

Women gave up the veil in the face of opposition from conservative folk. They began to enjoy equality of status with men. Turbans went the same way as women’s veils.

Resultant upon these changes was an enormous increase in the available supply of labour as women were given every assistance through the provision of crèches, kindergartens, polytechnics and feeding facilities at farm and factory. Besides those at the collective farms, 1,000 kindergartens had been established by 1951.

Ms Manton and her delegation visited the Stalin Cotton Mill in Tashkent. She says that the production techniques there were of the highest order and the factory was equipped with modern apartment houses, a departmental store a kindergarten, a canteen for meals, with a varied menu at low prices, a polyclinic, two cinemas and a "palace of culture" with complete amenities.

The Palace of Culture included a theatre for amateur dramatics, with 800 seats and 40 other rooms ministering to cultural needs.

No wonder, then, that there prevailed a spirit of enthusiasm and determination at the factory (and other work places) which helped in the fulfilment and over-fulfilment of the Five-Year Plans.

"The women of Uzbekistan, no longer confined to harems and subject only to the will of their menfolk as slaves with no rights, play a great part in the productivity of the State. Seventy per cent of the workers in factories of light industry are women, as are 20 per cent of the railway employees. Some women drive trains, 1,700 have mastered various railway techniques, and there are 100 women chairmen of collective farms. In the Stalin cotton factory the chief engineer ad the deputy director were women, and many women were Stakhanovite workers, habitually accomplishing more than the accepted norm." (p.79).

And what was true of Uzbekistan was equally true of the other Central Asian Republics.

Soviet successes

On the eve of the October Revolution, the peoples of Central Asia were oppressed and cruelly exploited, both by tsarism and by local exploiters – feudal lords, clergy, traders and money lenders, who incited the Central Asian peoples against each other in order to divide them and keep them in submission.

The Bolsheviks proclaimed the liberation of the oppressed people not merely on paper, as the bourgeoisie has often done, but in practice:

"To the old world", Lenin wrote, "the world of national oppression, national bickering, and national isolation, the workers counterpose a new world, a world of the unity of the working people of all nations, a world in which there is no place for any privileges or for the slightest degree of oppression of man by man" (‘The working class and the national question’, CW vol.19, p.92).

The nationalities policy of the socialist state was founded on the Leninist principle of "a voluntary union of nations – a union which precludes any coercion of one nation by another – a union founded on complete confidence, on a clear recognition of brotherly unity, on absolutely voluntary consent" (Lenin, ‘Letter to workers and peasants of Ukraine, CW vol.30, p.293).

As a result, the formerly oppressed peoples of the one-time colony of Central Asia began, after the establishment of Soviet power, to develop their national states. A hundred equal nations and nationalities lived in friendly relations with each other in Soviet Central Asia. Fraternal solidarity, mutual assistance and fruitful cooperation facilitated by the socialist system of economy and advanced forms of socialist production were the hallmarks of their life.

The best national traditions of each people were enriched by a new socialist content and were harmoniously combined with internationalist traits and traditions of the entire Soviet people.

Khan’s palace, Kokand

To begin with, imperialist propagandists, and their flunkeys of Central Asian origin, such as Mustafa Chokayev, former head of the so-called Kokand Autonomous government of Turkestan, insisted that no economic or cultural progress could be made by the peoples of Central Asia under Soviet rule. But Soviet reality belied these assertions, in view of which such a diehard anti-Soviet writer as Colonel Geoffrey Wheeler (retired), ex-chief at the time of the Central Asian Research Centre, the permanent editor of the Central Asian Review magazine, and an author of several books on Central Asia, was compelled to admit that:

"As regards their [Central Asian peoples] material condition there can be no doubt that during the forty years which have elapsed since the formation of the Muslim republics in Central Asia there has been a remarkable advance in public health, industrial productivity, cotton output, communications and the standard of living. In all these matters the Muslim peoples of Soviet Central Asia are far ahead of those of any non-Soviet Muslim country and indeed of any Asian country with the exception of Japan and Israel". Reluctantly admitting that there is national equality in the USSR, Wheeler wrote that the Muslims of Central Asia "have good reason to be satisfied with their present material condition" and that they accept the existing system of political arrangement (see G Wheeler, ‘Soviet Central Asia’, The Muslim World, October 1966, no.4, pp. 240-41).

Imperialist response

However, the success of the Soviet Union in solving the national question, far from pacifying Soviet critics, only angered them to distraction. What they have always been interested in is not the economic, social and cultural advance of the people, the fraternal harmony among the various nationalities, but only the undermining of the Soviet system.

The liberation by the Russian proletariat of the former colonial slaves of tsarism could not fail to shine a light on the plight of the colonial people elsewhere, who looked upon the developments in Central Asia as a shining example to follow. The greater the successes of the people of Central Asia in achieving equality and economic advance, the more these developments undermined the grip of various imperialist powers over their colonies – a fact recognised even by the The Spectator, a magazine which by no stretch of the imagination can be characterised as progressive. In an article written in connection with the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, it was obliged to state:

"… the real impact of the Russian Revolution on the outside world began to be felt only when decolonisation and the ‘modernisation’ of Afro-Asia got under way. How was one to modernise? … After 1917 the new generation of colonial revolutionaries … began to see Russia as their future model" (3 November, 1967, p.527).

The realisation of this reality made the imperialist powers even more frantic in their efforts to undermine Soviet power. In the changed conditions, imperialism decided on a policy of using the national question as an instrument and battering ram for attacking the Soviet system and weakening the unity of its peoples. Suddenly the sworn enemies of the self-determination of peoples decided to pose as staunch champions of self-determination of the peoples of Central Asia. Colonel Wheeler candidly admitted:

"Since, however, all the countries of the Western bloc regard the Soviet Union as a potential enemy, they are interested in the possibility of nationalism inside the Soviet Union … because they … think that widespread nationalist outbreaks would bring strategic and economic embarrassment to the USSR (op.cit., pp 148-9).

Hence the hurling with gay abandon of the accusations of ‘Russification’, ‘Sovietisation’ and ‘assimilation’, to lament the alleged lack of freedom to worship Islam and ‘restriction’ of the rights of Muslims, attempts at defaming the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Communist Parties of the Union Republics, accusations of ‘Soviet colonialism’ and the allegation that the constitutional right of the Central Asian republics to self-determination and to secede was merely ‘illusory’, being obviously of the view that this right would be real only if it was exercised in favour of secession rather than unity.

Who were these critics and falsifiers of Soviet policy?

The answer: who benefits?

The principal reason was the mounting prestige, the growing might, and increasing influence, of the socialist Soviet Union all over the world.

Having spent billions of dollars on armaments since the start of the Cold War, the US realised that it was losing the battle of ideas. With a view to correcting this imbalance, US imperialism, and following it other imperialist powers, made a point of establishing a new branch of study – Sovietology – in the Humanities departments of various universities and specially created institutes headed by anti-communists.

They created Radio Liberty in Munich. Established on 7 March 1952 on the initiative of the CIA, it spread ceaseless slander against Soviet Central Asia, broadcasting in Uzbek, Turkmenian, Tajik, Kara-Kalpak and Uighur, the principal languages of that part of the USSR.

Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty employed a large number of renegades and traitors who had fled to the West from the socialist countries, while all important posts were held by US intelligence officers. In their vile propaganda, these stations often drew on materials produced by the Central Asian Research Centre of St Anthony’s College, Oxford (UK). This so-called Research Centre, founded in 1951, operated with the support, and under the control, of British intelligence. Apart from this Centre’s director, Colonel G Wheeler, and its secretary, both of whom were SIS officers, not a single member of this organisation knew of its association with British intelligence. The focus of this institute was to study the political and cultural development of six Central Asian Soviet Republics – Azerbaijan, Turkmenia, Uzbekistan, Tajikstan, Kirghizia and Kazakhstan – all with Muslim populations. The Centre’s director was responsible to the Deputy Chief of the SIS.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, this dirty work was carried out under the leadership of Boris Meissner, a war criminal and fanatical Nazi who admired Hitler and the Nazi ‘new order’, but who sadly escaped punishment at the Nuremberg trial of Nazi criminals because the revanchist circles in West Germany protected him.

He was given academic posts, which he used to propagate anti-Soviet views, professing ‘concern’ about human rights of the people of Central Asia and the Baltic Republics to self-determination. His colleagues and students would surely have been shocked to discover that this mild-mannered anti-Soviet theoretician had been a practised torturer and murderer of Soviet citizens in Leningrad during the Second World War.

Another despicable character on the payroll of the imperialist intelligence services was Mustafa Chokayev – the first to launch an attack on the nationalities policy of the CPSU in Central Asia. He had been the head of the so-called Kokand Autonomous government which had a life of a few months in 1917 and 1918 in a town of the Ferghazia Valley – a ‘government’ with absolutely no ties with the general population. A bourgeois nationalist, he served the interests of the united counter-revolutionary forces of the Russian capitalists, local exploiters and the British in return for support. After being defeated, he made his way to Paris. Towards the end of the 1920s he moved to Berlin where, in 1929, being an avowed enemy of the Soviet Union, he was permitted to launch the Turkic language magazine, Yash Türkistan. With Hitler’s ascent to power his activities attracted Nazi interest. The latter assigned Chokayev a special role as the Nazis prepared for war against the USSR.

Having launched the war against the USSR, the Nazis created the so-called Unity Committee of National Turkestan with the sole purpose of conducting extensive subversive activity against Soviet power. They made Chokayev president of the Committee.

As he did not live up to the expectations of his Nazi masters, they got rid of him. He was poisoned in 1942 and his place was taken by Vali Kajum-Han, a traitor who had fled his country, and whose right-hand man was none other than Baymirza Hayit, a cut-throat who had the dubious distinction of serving the Nazis during the war. He settled down in Munich after the war, from where he began serving the American propaganda machine which, in the cynical words of the Chairman of the Political Information Committee, General Jackson, in its ideological struggle against communism, needed not the truth but subversion. In this war, he said, we shall need all the cut-throats and gangsters whom we can manage to recruit.

Explanation of the Soviet achievements on the national question

The answer lies in the science of Marxism-Leninism and the adherence by the Soviet Union to this science.

Marxism and national liberation

Marxism teaches us that the concepts of ‘nationality’ and ‘nationalism’ were the products of the era of the rise of capitalism and were closely connected with the division of society into two basic classes, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and the class struggle. The abolition of national oppression depends on the outcome of this struggle inasmuch as national oppression is a manifestation of the class domination of the bourgeoisie:

"In proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another is put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end" (Marx and Engels 1848, The Manifesto of the Communist Party, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1965, p.55).

The international alliance of the proletariat, and consequently its own social emancipation, were impossible without first demolishing the wall of enmity and isolation between nations, which had been created by the bourgeoisie.

"Any nation that oppresses another forges its own chains", wrote Marx on 28 March 1870. In a letter to S Meyer and A Vogt of 9 April 1870, Marx noted that the working class of Britain was "divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians", and he stressed that it was crucial "to awaken a consciousness in the English workers that for them the national emancipation of Ireland is no question of abstract justice or humanitarian sentiment but the first condition of their own social emancipation" (K Marx and F Engels, Selected Correspondence, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1975, p.222-23).

This is the only way to ensure the international class alliance of the workers essential for the victory over their class enemy, the bourgeoisie.

Twelve years later, in his letter to Kautsky, Engels wrote to say with reference to the future that "the victorious proletariat can force no blessings of any kind upon any foreign nation without undermining its own victory by so doing" (Ibid. p.331).

Lenin, living in the era of imperialism and proletarian revolutions, was the first to perceive, predict, and theoretically substantiate the role and significance of the future national liberation movements of the peoples of backward countries for the development of democracy and the victory of socialism and their interconnection with the struggle of the working class for socialism. He was able to persuade the Second Congress of the RSDLP in 1903 to include "a right of self-determination for all nations making up the state" in its programme, and he fought for its retention against much opposition from sections of his party.

Over a period of two decades, Lenin never stopped stressing the importance of close connections between the struggle of the proletariat for emancipation and the struggle of oppressed nations for their liberation. He never ceased to exhort the proletariat of the oppressing nations to realise the significance of, and need to support, the national liberation movements of the oppressed peoples. Speaking at the Second Congress of the Communist Organisations of the Peoples of the East, pointing to the signs of an approaching powerful upsurge of the revolutionary struggle in the East, Lenin said:

"The period of the awakening of the East in the contemporary revolution is being succeeded by a period in which all the Eastern peoples will participate in deciding the destiny of the whole world so as not to be simply objects of the enrichment of others. The peoples of the East are becoming alive to the need for practical action, the need for every nation to take part in shaping the destiny of all mankind" (22 November 1919, CW vol 30, p. 160).

Speaking at the Second Congress of the Comintern, this is how Lenin urged the proletariat of the imperialist countries to unite with the oppressed peoples in the struggle against imperialism:

"The revolutionary movement in the advanced countries", he said, "would actually be a sheer fraud if, in their struggle against capital, the workers of Europe and America were not closely and completely united with the hundreds upon hundreds of millions of ‘colonial’ slaves who are oppressed by capital" (CW vol 31, p.271).

In the following year Lenin returned to this question at the Third Congress of the Comintern. Admonishing those who did not put much faith in the national liberation movement, he pointed out:

"… Millions and hundreds of millions, in fact the overwhelming majority of the population of the globe, are now coming forward as independent, active and revolutionary factors. It is perfectly clear that in the impending decisive battles in the world revolution, the movement of the majority of the population of the globe, initially directed towards national liberation, will turn against capitalism and imperialism and will, perhaps, play a much more revolutionary part than we expect" (5 July 1921, CW vol. 32, pp.481-2).

In his preliminary draft theses on the national and colonial questions, Lenin dwelt on the national policy of the Communist International and he wrote that its "… entire policy on the national and colonial questions should rest primarily on a closer union of the proletarians and the working masses of all nations and countries for a joint revolutionary struggle to overthrow the landowners and the bourgeoisie. This union alone will guarantee victory over capitalism, without which the abolition of national oppression and inequality is impossible" (June 1920, CW vol.31, p.146).

Lenin emphasised the world-historic significance of proper relations between the hitherto oppressed peoples of Central Asia and the young Russian Soviet Republic in these words:

"It is no exaggeration to say that the establishment of proper relations with the peoples of Turkestan is now of immense, epochal importance for the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic.

"The attitude of the Soviet Workers’ and Peasants’ Republic to the weak and hitherto oppressed nations is of very practical significance for the whole of Asia and for all the colonies of the world, for thousands and millions of people" (From Lenin’s letter ‘To the Communists of Turkestan’, November 1919).

The Tenth Party Congress defined the tasks of the Party on the national question, giving the following description of the policy of tsarism in Russia’s periphery:

"The policy of tsarism, the policy of the landowners and the bourgeoisie with regard to these peoples was designed to stifle all rudiments of statehood, cripple their culture, check the development of their language, keep them in ignorance and, finally, Russify them as much as possible. This policy accounts for the undeveloped state and the political backwardness of these peoples" (CPSU in Resolutions, part 1).

Concerned with speeding up the development of the peoples of backward regions to the level of the advanced parts of the country, Lenin pointed out on 31 December 1922 that "internationalism on the part of the oppressors or ‘great’ nations, as they are called (though they are great only in their violence, only great as bullies) must consist not only in the observance of the formal equality of nations but even in an inequality of the oppressor nation, the great nation, that must make up for the inequality which obtains in actual practice. Anybody who does not understand this has not grasped the real proletarian attitude to the national question, he is still essentially a petty bourgeois in his point of view … In one way or another, by one’s attitude or by concessions, it is necessary to compensate the non-Russians for the lack of trust, for the suspicion and the insults to which the government of the ‘dominant’ nation subjected them in the past" (31 December 1922, ‘The question of nationalities or "autonomisation"’, CW vol.36 p.608).

The economic development of Central Asia had to take place at a faster pace than in the rest of the country. This necessitated a systematic, long-term, centralised redistribution of national income in favour of the backward border regions. The brunt of the burden was to be borne by those who produced a proportionately bigger share of the national income. This was true proletarian internationalism in action.

"We are now exercising our main influence on the international revolution through our economic policy … The struggle in this field has become global", said Lenin (28 May 1921, speech at the closing of the Tenth All-Russia Conference of the RCP(B), CW vol.32 p.437).

Even bourgeois sources were obliged to admit the spectacular success of Soviet industrialisation:

"The speed with which Russia achieved industrialisation is probably the Soviet system’s most impressive accomplishment – without it, it’s doubtful whether the Communist regime would have survived". So wrote Business Week of 29 April, 1967, in an article on the 50th anniversary of the establishment of Soviet power.

We conclude with the following quotation from J V Stalin:

"The October Revolution has shaken imperialism not only in the centres of its domination, not only in the ‘metropolises’. It has also struck at the rear of imperialism, its periphery, having undermined the rule of imperialism in the colonial and dependent countries.

"Having overthrown the landlords and the capitalists, the October Revolution broke the chains of national and colonial oppression and freed from it, without exception, all the oppressed peoples of a vast state. The proletariat cannot emancipate itself unless it emancipates the oppressed peoples. It is a characteristic feature of the October Revolution that it accomplished these national-colonial revolutions in the USSR not under the flag of national enmity and conflicts among nations, but under the flag of mutual confidence and fraternal rapprochement of the workers and peasants of the various peoples in the USSR, not in the name of nationalism, but in the name of internationalism.

"It is precisely because the national-colonial revolutions took place in our country under the leadership of the proletariat and under the banner of internationalism that pariah peoples, slave peoples, have for the first time in the history of mankind risen to the position of peoples that are really free and really equal, thereby setting a contagious example to the oppressed nations of the whole world.

"This means that the October Revolution has ushered in new era, the era of colonial revolutions which are being carried out in the oppressed countries of the world in alliance with the proletariat and under the leadership of the proletariat.

"It was formerly the ‘accepted’ idea that the world has been divided from time immemorial into inferior and superior races, into blacks and whites, of whom the former are unfit for civilisation and are doomed to be objects of exploitation, while the latter are the only bearers of civilisation, whose mission it is to exploit the former. This legend must now be regarded as shattered and discarded. One of the most important results of the October Revolution is that it dealt that legend a mortal blow, by demonstrating in practice that the liberated non-European peoples, drawn into the channel of Soviet development, are not one whit less capable of promoting a really progressive culture and a really progressive civilisation than are the European nations.

"It was formerly the ‘accepted’ idea that the only method of liberating the oppressed peoples is the method of bourgeois nationalism, the method of nations drawing apart from one another, the method of disuniting nations, the method of intensifying national enmity among the labouring masses of the various nations. This legend must now be regarded as disproved. One of the most important results of the October Revolution is that it dealt that legend a mortal blow, by demonstrating in practice the possibility and expediency of the proletarian, internationalist method of liberating the oppressed peoples, as the only correct method; by demonstrating in practice the possibility and expediency of a fraternal union of the workers and peasants of the most diverse nations based on the principles of voluntariness and internationalism. The existence of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which is the prototype of the future integration of the working people of all countries into a single world economic system, cannot but serve as direct proof of this.

"It need hardly be said that these and similar results of the October Revolution could not and cannot fail to exert an important influence on the revolutionary movement in the colonial and dependent countries. Such facts as the growth of the revolutionary movement of the oppressed peoples in China, Indonesia, India, etc., and the growing sympathy of these peoples for the USSR, unquestionably bear this out" (‘International character of the October Revolution’, speech delivered on the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution).