Stalin’s Library by Geoffrey Roberts – a resumé and review – Part 2

We continue Harpal Brar’s review of Geoffrey Roberts’ book on Stalin’s library, as Harpal had completed it in full before he died in January this year after only one instalment had been published (in the January/February issue). Space did not allow for continuation in the March/April issue, but we are now delighted to be able to continue the serialisation of this interesting work which will run to several parts.

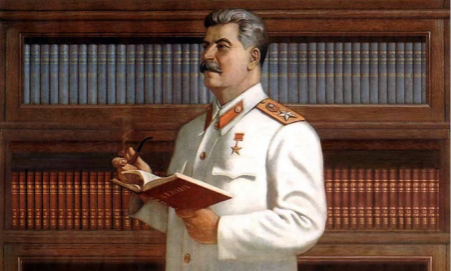

Stalin at work while in exile

As he spent several years in exile, and opportunities for political activity were limited, it provided him with plenty of time for study. He spent much time in local libraries.

In February 1912 he disappeared from his lodgings in Vologda (northern Russia), leaving behind his books on a variety of subjects, ranging from arithmetic, and astronomy to philosophy. Many of the texts included works by or about Voltaire, Auguste Comte, Karl Kautsky, etc.

His longest exile, from 1913 to 1917, was to Turukhansk in Siberia, a harsh place of detention, and he was often suffering from ill health. He complained about the conditions to his comrades and friends and asked for their financial support. But most of all he repeatedly asked them to send him books and journals, especially those to enable him to continue his studies on the national question.

It was Marxist literature that most preoccupied him, especially the works of Marx and Engels. His first published work was a series of articles on Anarchism or Socialism? (1906-7) in which he deployed Marxist arguments against anarchist philosophy. In his ‘Marxism and the national question’ (1913), he subjected to criticism the so-called Austro-Marxist view that nations were a psychological construct rather than historical entities based on land, language and economic life. Apart from Lenin, says Roberts, his favourite Russian Marxist was Georgi Plekhanov, the father of Russian Marxism, whose ‘The Monist view of history’ Stalin read again in later life.

His famous 1913 treatise on Marxism and the national question was published in three parts in the pro-Bolshevik journal Prosveshchenia (Enlightenment) and signed K Stalin, a pseudonym he had just begun to use but which became permanent and replaced Koba as his underground party name. This pamphlet was to become the basis of the Bolshevik policy after the October Revolution and greatly facilitated the solution of the complicated question of nationality in a country that comprised scores of nations and nationalities, with their own languages, culture and traditions.

As the First World War broke, almost all the social-democratic parties deserted the camp of the proletariat for that of the bourgeoisie, i.e., adopting the slogan of ‘Defence of the fatherland’. The Bolsheviks under Lenin’s leadership not only opposed the war but, on the contrary, called upon the socialists of various countries to work for the defeat of their own country and turn the war into a civil war for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and pave the way for revolution in Russia and all the belligerent states. This policy brought about the Great Socialist October Revolution in Russia, while the bourgeoisie stayed put in other European countries thanks to the betrayal of Social Democracy.

Lenin returned to Russia from Switzerland in April 1917 to insist on outright opposition to the war and to the provisional government that had been set up after the fall of the Tsar, Nicholas II (the February Revolution).

During the most tumultuous, and world historic, months following the February Revolution, Stalin sided with Lenin at every major turning point. He too, like Lenin, believed that the Russian revolution could be the catalyst for a European and worldwide revolution: “The possibility is not excluded”, he said, “that Russia will be the country that will lay the road to socialism… and must discard the antiquated idea that only Europe can show us the way. There is dogmatic Marxism and creative Marxism. I stand for the latter” (Works, Vol 3, pp.199-200).

The October Revolution and the civil war

Many Trotskyite and ordinary bourgeois historians have indulged in gossip to the effect that Stalin was an unimportant figure in the months leading up to the October Revolution (7 November). Roberts puts the record straight:

“Though overshadowed by Trotsky in historical memory, there were few Bolshevik leaders more important than Stalin in 1917. One of the first Bolshevik leaders to reach Petrograd from exile, he was a member of the editorial board of the party’s newspaper Pravda, contributing numerous articles to the Bolshevik press. When Pravda was suppressed by the authorities, he edited the paper issued by the party as a substitute. When the provisional government clamped down on the Bolsheviks in the summer of 1917, and Trotsky was gaoled, while Lenin had fled to Finland, Stalin remained at large. He spoke at all the party’s major meetings in Lenin’s absence and presented the main report to the 6th Congress of the Bolshevik Party in July-August 1917. This was a tough assignment, coming as it did in the wake of the party’s setbacks following the demonstrations of the July days that had provoked the provisional government’s crackdown. Stalin supported Lenin’s proposal for an insurrection and was one of seven party members entrusted with overseeing its preparation. As Chris Read puts it, ‘if Stalin was a blur it might seem to be a result of his constant activity rather than indistinctiveness’” (pp.55-56).

Having seized power, the Bolsheviks were determined to hold on to it at all costs. In March 1918, Lenin’s government signed the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty with Germany and her allies. The negotiations leading to the treaty provoked a deep split in the Bolshevik leadership and broke up the alliance with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries.

One of the first decrees of the Soviet government had been a proclamation on peace which called for a general armistice and negotiation for a “swift end and democratic peace”, i.e., peace without annexations. When the fighting continued, Lenin agreed to sign a separate peace with the Germans and started the negotiations at Brest-Litovsk. Trotsky, the Commissar for Foreign Affairs, led the Soviet delegation. In violation of the Soviet government’s mandate to sign the treaty, he adopted the formula ‘neither war nor peace’ and a unilateral end to hostilities.

Trotsky aimed to spin out the negotiations and use them as a platform for propaganda in the erroneous belief that it would provoke a European revolution. Both Lenin and Stalin were in favour of accepting German terms, as the alternative was losing the war and, with it, the revolution. Opposed to this were Nicolai Bukharin and ‘left communist’ supporters of a revolutionary war against Germany, who argued erroneously that the European proletariat would rise in support of revolutionary Russia. The Left Socialist Revolutionaries were also in favour of continuing the war.

Germany played along with Trotsky’s charade for a while but in January they issued an ultimatum that demanded the annexation of large territories of the western areas of the former Tsarist empire in return for a peace deal. The Russian armies were exhausted and in no position to continue the war. Faced with imminent collapse on the front, the Bolshevik government had little choice but to sign the peace treaty, which now contained far harsher terms than the original ones, for which Trotsky and the ‘left communists’ were entirely to blame.

The conclusion of the First World War in November 1918 was followed by the civil war and the war of intervention, in which the ‘white armies’ led by former generals and admirals, supported by the interventionist imperialist armies, did their best to overthrow the Bolshevik government. The civil war was a close run thing. However, the Soviet government managed to raise a 5-million strong Red Army which was in the end destined to prevail.

During the war, Stalin played “a very important role in providing direction on crucial fronts. If his reputation as a hero was far below Trotsky’s, this had less to do with objective merit than with Stalin’s lack of flair for self advertisement” (L McNeal, Stalin: man and ruler, p.63, cited in Roberts p.57).

“During the civil war, Stalin was Lenin’s troubleshooter-in-chief at the front line” (p.57).

A little earlier, in June 1918, he was sent to Tsaritsyn (renamed Stalingrad in 1924) to protect food supply lines from southern Russia. With the city about to fall to the enemy, he responded by harsh measures against those deemed disloyal and traitorous. He was incensed by the attempted assassination of Lenin by the Socialist Revolutionary Party member, Fanny Kaplan, in August 1918. Stalin cabled to Moscow that he was responding to this ‘vile’ act by “instituting open and systematic mass terror against the bourgeoisie and its agents” (Reed, quoted by Roberts at p.57).

In January 1919 he was sent to the Urals to investigate why the Perm region had fallen to Admiral Kolchak’s White Army. He was accompanied by Felix Dzerzhinsky, the formidable head of Cheka – the agency for countering counter-revolutionaries. This, they reported, was due to the defection of a number of former Tsarist officers to the Whites.

In the spring, Stalin was sent to bolster the defence of Petrograd, which was threatened by General Yudenich’s White Army based in Estonia. For months he was a highly visible figure of authority in the Petrograd area, touring the front line and inspecting military bases.

Stalin played a significant role in bolstering the southern front against General Denikin’s troops in October 1919. His next assignment was the south-west front, threatened by the newly-independent Polish state in April 1920, which was threatening to cross the Curzon line (the boundary between Poland and Russia) in order to grab as much territory as possible while civil war raged in Russia. The Poles won that contest and Soviet Russia was forced in March 1921 to sign the Treaty of Riga which inflicted severe territorial losses on Soviet Russia, including the incorporation of western Belorussia and western Ukraine into Poland. At the 9th Party Conference in September 1920, Stalin was criticised for errors during the Polish campaign. He responded with a dignified statement pointing to his publicly-expressed doubts about the ‘march on Warsaw’ and reiterated his call for a Commission to examine the reasons for the Soviet defeat.

By this time Stalin had, at his own request, been relieved of military responsibilities. By the time the civil war was over, with the White armies and the imperialist interventionist forces having been beaten, he had plenty of work to do. Throughout the civil war he had continued to be the Commissar for Nationalities. In addition, in March 1918, he was appointed to head the People’s Commissariat of State Control, which was later renamed the Worker-Peasant Inspectorate, charged with protecting state property and keeping officials under control.

Appointment as General Secretary

Georgia, ruled by the Mensheviks, was the source of serious differences between Lenin and Stalin, with Lenin favouring a more conciliatory approach to the Georgian nationalists. In the end Stalin’s approach prevailed, with the Red Army marching into Georgia in February 1921.

Despite differences over the Polish and Georgian questions, at Lenin’s insistence Stalin was appointed the General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1922. In view of his experience, his intellectual ability, and his steadfast loyalty to the Party and Lenin, it made a lot of sense to appoint him to this post, which carried tremendous responsibility and an enormous burden of work.

At the 10th Party Congress in March 1921, Stalin supported Lenin in the dispute with Trotsky on the question of the role of Soviet trade unions, as he did over the introduction of the New Economic Policy – which marked the Party’s retreat from ‘war communism’ of the civil war period. And, as a consistent supporter of Party unity, he supported the ban on the formation of factions in the Party – groups in the Party that operated their own internal organisation, rules and discipline.

The resolution was to be resented by the opposition group for years afterwards. In May 1922, Lenin suffered the first of a series of debilitating strokes.

Socialism in one country

After Lenin’s death in January 1924, Stalin emerged as the pre-eminent leader of the Party. Among his demonstrated and administrative capabilities was his ability to inspire in the Party a vision of a bright future through the building of socialism in the USSR, as envisioned and argued for by Lenin. By insisting, as had Lenin, that socialism could be built in the Soviet Union even in the absence of a European revolution, Stalin gave meaning to the lives of Party members and the broad masses of Soviet people. While admitting this, Roberts cannot resist propagating the lie spread by Trotskyists and bourgeois historians that in pursuing the building of socialism in the USSR Stalin was departing from Leninism, and that in doing so he was “…prioritising the construction of socialism at home over the spread of revolution”.

The theory of socialism in one country – the USSR – has nothing to do with Stalin. It is a theory, as any well-informed person knows, given birth to, and followed, by Lenin. Stalin was doing no more than faithfully following the steps of Lenin. Roberts’ assertion that “the failure of the revolution to spread abroad prompted Stalin to fashion a NEW DOCTRINE – SOCIALISM IN ONE COUNTRY” [emphasis added] is totally false, while his statement that they “proclaimed that Soviet Russia could build a socialist state that would safeguard both the Russian Revolution and the future world revolution” (p.64) is perfectly correct.

Stalin correctly stated in 1927: “an internationalist is one who is ready to defend the USSR without reservation, without wavering, unconditionally; for the USSR is the base of the world revolutionary movement, and this revolutionary movement cannot be defended and promoted unless the USSR is defended” (Works, Vol 10, p.53).

The tragic demise of the Soviet Union has served to prove the correctness of Stalin’s statement.

At a time when the anticipated European revolution had failed to materialise, the construction of socialism, far from contradicting the spread of revolution, was the only means of spreading it, as subsequent events were to prove. The strong Soviet state, through its Five-Year Plans, with their spectacular results, and collectivisation, became a base for world revolution. The alternative would have been to shut up shop or send the Red Army into Europe allegedly to spread revolution – both courses would have had catastrophic consequences hardly conducive to world revolution. And yet, that is where the counter-revolutionary theory of so-called ‘permanent revolution’ would have led. No socialism in the USSR and no revolution elsewhere. (For details on this and related questions see Harpal Brar, Trotskyism or Leninism?).

Roberts writes: “Stalin’s workload as general secretary was enormous and continued to grow … The paper trail of reports, resolutions and stenograms passing through his office were endless, as were the frequent visitors, and the numerous meetings he had to attend” (pp 64-6).

His leadership in the construction of socialism, which enabled to country to shed its medieval integument, and join the ranks of highly industrialised countries, his inspiring role as the commander-in-chief of the Red Army that routed the allegedly invincible German army, resulting in the crowning victory of the Soviet Union in the Great Patriotic War – a victory which, in addition to freeing the USSR from the Nazi hordes, brought liberation to the peoples of eastern and central Europe – will forever remain an eloquent proof of his correct line and leadership of the world communist movement. People all over the world owe a debt of gratitude to Stalin, and the USSR which he led, for their role in liberating humanity from the jackboot of German fascism and for weakening imperialism.

Setting up the library

In May 1925, Stalin entrusted his staff with the task of classification of his personal book collection, with the request that the books be classified not by author but by subject matter. The list of subjects to be classified is simply staggering, ranging from philosophy, political economy, Russian history, history of other countries, to military affairs., the national question, the history of revolutions in other countries, the February and October Revolutions of 1917, Lenin and Leninism, the history of the Russian Communist Party and the International, fiction, art criticism, political and scientific journals. Excluded from this classification and to be arranged separately were books by Lenin, Marx, Engels, Kautsky, Plekhanov. Trotsky, Bukharin, Zinoviev, Kemenev, Lafarge, Luxemburg and Radek.

All the rest, he instructed could be classified by author.

His grandiose scheme envisaged a grandiose personal library, “one that could contain a vast and diverse store of human knowledge, not only the humanities and social sciences, but aesthetics, fiction and natural sciences. His proposed scheme combined conventional library classification with categories that reflected his particular interests in the history, theory and leadership of revolutionary movements, INCLUDING [emphasis added] the works of anti-Bolshevik socialist critics such as Karl Kautsky and Rosa Luxemburg, as well as the writings of internal rivals such as Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev. Although pride of place went to founders of Marxism – Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and to its pre-eminent modern exponent, Vladimir Lenin” (p.68).

Stalin’s library was a personal working archive that “sprawled across his offices, apartments and dachas” (p.71). From the early 1920s he had accommodation and his office in the Kremlin and another working space just a few miles away in the Party’s central committee building on Staraya Ploshchad (Old Square).

During meetings, “Stalin was fond of plucking a volume of Lenin’s off the shelves, saying ‘Let’s have a look at what Vladimir Ilyich has to say on this matter’. Stalin’s daughter Svetlana recalled that, in his Kremlin apartment, there was no room for pictures on the walls – they were lined with books” (p.71).

TO BE CONTINUED