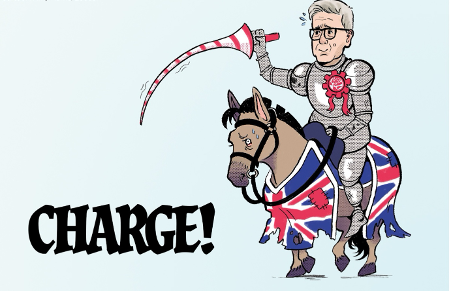

Starmer’s failing militarism

As British imperialism slides further into crisis, its political leaders try to cover up this decline by making ever more grandiose pronouncements as to their ability to still “project power” into the world. The declarations made by Sir Keir Starmer regarding his willingness to send British forces to Ukraine should be seen in this light. Since it became clear that the Ukraine war was sliding towards an ignominious defeat for the Nato-backed forces of the Kiev regime, the US under the Trump administration has been trying to play a double game. On the one hand it has been engaging the Russians in negotiations and talking about ‘restoring relations’ with them. On the other it has been pushing the Europeans to (effectively) carry on with the ever-escalating aggressive actions against Russia. Amidst all of this, Sir Keir Starmer calls for a huge programme of expansion of the British military. He is supported in his calls for this by the usual collection of social chauvinist trade union leaders (such as Unite General Secretary Sharon Graham) welcoming the creation of ‘good jobs’ in the arms manufacturing industries. Starmer has also stated that he is determined to increase military spending. There is a large gap, though, between the grandiose pronouncements of the leaders of British imperialism and the actual reality of what decaying, late stage British imperialism can actually do.

Post Cold War military doctrines

The British imperialists realised that large armies were too expensive to maintain as the colonial period of British imperialism came to a close. Being forced out of India, Malaya, Kenya and other colonies meant military tactics needed to change. The British ruling class did away with conscription in 1960 and slowly cut back their forces on land in particular over the next thirty years. Their policy was driven by the need to move from the direct colonialism of the old school to the neo-colonialism of the modern era. Neo-colonialism demands a shift from direct military occupation of a nation to rule via more hidden means. Many African nations gained their independence from British and French colonialism during this time, but were tied into economic relationships with their former coloniser which was enabled to retain effective control over the economies of the nominally independent states. This meant that the British were able to downgrade their military forces to specialise more on providing training and direction of operations rather than doing the bulk of the fighting using British troops. This was advantageous for the British ruling class as the fewer troops from the imperialist homeland killed in action, the less likely was the rise of a more powerful anti-war movement within Britain itself. The only time the British were willing to risk a ground war was when there was little chance of widespread casualties, as was the case with Iraq in 1991 and 2003. In the first Gulf War Iraq was facing such overwhelming odds that the fighting was over relatively quickly, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq took place after over a decade of siege sanctions had severely weakened the Iraqi state and military – to the point where the US and British imperialists were fairly confident they could get away with minimal casualties. The domestic backlash to the Iraq war and the inability of the imperialists to subdue the Iraq resistance forces, and the military cutbacks necessitated by the economic collapse of 2008, caused British war planners to change things again for the purpose of the wars in Libya and Syria. In the case of the US, British and French war of aggression against Libya, the imperialists used their air forces but for their ground forces they relied upon armed gangs organised by the Saudis and the Gulf state tyrannies. The role of the British in the Libyan and Syrian wars was to run psychological operations, deploy ‘special forces’ and to organise the siege of Syria via the sanctions regime. The actual fighting was done by what are, essentially, mercenary armies that work for imperialism. Ukraine was another case of the US and British successfully turning an entire country into an outsourced military with the British in the role of planners of the military campaign against Russia (as even The Times now admits) with the Ukrainians dying in gigantic numbers to enact the (often extremely foolish) plans of British military officers. In 65 years, the British imperialists have gone from having large-scale land, sea and air forces to having much smaller forces which are more focused on managing other (largely non-British) forces.

The failure of the Ukraine war, though, has caused a panic within the corridors of the British Ministry of Defence. The British operation in Ukraine was supposed to revive British imperialism by causing either the collapse of Russia or the restoration of comprador rule there. This aim having failed, the Starmer government is having to reconsider its options. Added to the complications facing the British ruling class is the fact that there is a very public reconsideration of priorities going on (chaotically) inside the Trump administration. Trump has demanded that the rest of the Nato countries increase defence spending to 5% of GDP and that more weapons orders are placed with US companies by these same countries. In response to this Starmer has announced a 2.5% increase in spending, up to from 2.3%, with an ‘ambition’ to reach 3% of GDP by 2029. This is of course far away from Trump’s demands and highly unlikely to produce anything that will give either the Russians or Chinese sleepless nights.

The British military chiefs know very well that they are utterly incapable of challenging the Chinese or the Russians either now or in five years. This is why The Times ran an article on 24 April announcing that Starmer’s much trumpeted threats to deploy British troops to Ukraine as ‘peacekeepers’ has been an absolute non-starter, as the risks of them being attacked by the Russians were much too high (see Larisa Brown, ‘UK could scrap plans to send thousands of troops to Ukraine’).

Imperialism undermined by its own degeneracy

Starmer’s plans for an increase in production of war materiel are undermined by the parlous state of the British industrial base. Britain does not produce enough steel, for instance, to meet the demands of war production. The Labour government stepped in at the last minute only to prevent the Scunthorpe steel plant from closing because it supplies vital parts to Network Rail that would be difficult to source from elsewhere. But re-nationalising one steel plant is hardly going to be enough if the rhetoric of Starmer is to be believed about his plans to reinvigorate war production. Britain, being the oldest imperialist country, also makes it by far the most degenerated. Its industrial base has been allowed to wither away to the point where the militarily necessary mass production of tanks, ships and aircraft is simply not possible. The Ukraine war has seen Britain’s reserve stocks of weaponry and vehicles get almost exhausted as a result of the massive destruction that the Russian army has inflicted upon the Ukrainian/NATO forces. This is where we see the contradictions of decaying imperialism on full display. The British ruling class has wiped out large-scale industrial facilities in Britain in pursuit of the greater profits they could secure by exporting their capital abroad. Therefore the only way that the imperialists can secure the necessary boost in production would be to have the state take direct control over industry to build up industrial capacity in a way that the private owners will not do. The reality behind Starmer’s big statements is that the British ruling class would never accept the tax rises that would be needed to build back the industrial base since these would be far too great simply to be imposed on the working class and would therefore have to be financed largely by big business.

The dangers ahead

Faced with defeat and disaster in Ukraine, the British ruling class will not only increase their aggression against other nations but the class war within Britain itself will intensify. As British imperialism weakens, it will become harder and harder for the bourgeoisie to maintain its necessary rates of profit, so the ruling class will be compelled, to try to make good by squeezing the working class harder and harder, forcing the working class to resist. We can expect the bourgeoisie to launch ever greater attacks upon the working class in the form of wage cuts, privatisations and price hikes. To weaken working-class resistance, it is necessary to keep them divided, so we can expect to see an increase in attempts at stoking bourgeois nationalism, rabid anti immigration and anti Islam sentiment being whipped up and attempts to indoctrinate the younger generation of workers with militarism. This must be resisted, and communists must explain clearly to workers who might be taken in by this that for all the tub-thumping and flag waving of the British imperialists, their appeals to nationhood and ‘pride’ are, in reality, merely an attempt to disguise the rabid pursuit of profit by a ruling class whose time ran out over a century ago. The British working class must come to understand that their greatest enemies sit in the City of London and that we share these enemies with all those resisting imperialism. Only by learning this lesson can British workers hope to free ourselves from the shackles placed on us by imperialism.