India-Pakistan-Kashmir – A 78 Year Old Wound

The long history of armed clashes between India and Pakistan in the disputed region of Kashmir added another incident to this bloody history in the form of a series of clashes which carried on bwtween 22 April and 10 May this year. The latest flare- up occurred when the group known as the ‘Resistance Front’, an offshoot of Lashkar-e-Taiba, carried out a massacre of Hindu tourists in Pahalgam, in Indian-controlled Kashmir. The Indian government, headed by Narendra Modi of the BJP, immediately accused Pakistan of being complicit in this attack and took a series of actions that led to exchanges of artillery fire and air battles between the Pakistani and Indian air forces.

Background

The disputed status of Kashmir stems from its incorporation into India as part of the partition of the country in 1947 but the origins of the conflict arose earlier during the rule of the British East India company. The formation of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir came about after the East India company forces defeated the Sikh Empire and forced it to cede the Kashmir valley to the British under the terms of the Treaty of Amritsar of 1846. This was then sold to Gulab Singh, a former nobleman in the court of the Sikh maharaja, Ranjit Singh, ruler of the Sikh Empire. Gulab Singh, a Hindu of the Rajput Dogra clan, had sided with the British in the war, and he founded the Dogra dynasty that ruled over Kashmir as a state within British occupied India until Independence in 1947.

As was always the case in the princely states of British India, the great majority of the peasants who made up the population of Kashmir were Muslim while the puppet princes who ruled it were Hindu. This is part of what created the dispute after Indian independence and the partition of the country. The decision to split on religious lines what had been British occupied India into two states, India and Pakistan, was one that the imperialists were keen on. The British were forced out of India following multiple revolts of the masses that spread to the Indian army, which the Raj had relied upon for controlling the vast territory of India. When confronted with the fact that they could no longer rely upon Indian troops to follow orders any more, the British prepared to leave, but not before they created as many problems as possible in order to disrupt the development of the country after they left. Capitalising upon divisions they had fostered between Hindus and Muslims, the British jumped at the chance of partitioning the country into majority Hindu and majority Muslim areas.

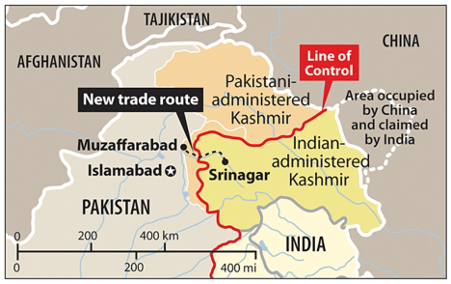

The last Maharaja of Kashmir, Hari Singh, opted to join India in 1947, but this was immediately countered by the newly independent government of Pakistan which sent irregular forces in to try and seize Kashmir. The 1947 war ended in a stalemate but with the Indian government controlling the bulk of the territory.

There were further wars over Kashmir fought between India and Pakistan in 1965 and 1999 which saw minimal changes in the land held by either side. The fact that, almost 80 years on from independence, the border dispute still has capability of provoking a war tells us that the tactic of British imperialism in splitting the country in two is still paying dividends for imperialism. The purpose of partition, from the British point of view, was to create exactly the kind of long-running dispute that has emerged to destabilise both countries and to fuel religious sectarianism as well. States which are locked into a war mentality based on religious sectarian strife are unable to develop to their full potential. The imperialists know this very well which is why, when forced to concede independence, they work to make sure that the independent state has as many religious, ethnic and territorial disputes within it as possible. It is notable that although Lord Louis Mountbatten was the individual royal representative in the Raj. sent to oversee independence and partition, it was the allegedly ‘socialist’ and NHS-creating ‘Labour’ government of Clement Attlee that was in government in Britain at the time of the great division in 1947 – which resulted not only in lasting destabilisation but in contemporaneous pogroms causing millions of deaths.

This sectarianism has been a policy gladly seized upon by the ruling classes of both countries (and of many political stripes, including their representatives in Congress and BJP alike, inter alia) in their own efforts to divide and rule as they continue ruthlessly to exploit the Indian and Pakistani working class and peasantry.

The latest clash

Following the attack on tourists in Pahalgam, the Indian government accused the Pakistani government of being behind it. Successive Indian governments have made accusations against the Pakistanis of sponsoring irregular forces such as the ‘Resistance Front’ and Lashkar-e-Taiba which have been carrying out attacks against security forces and civilians in Kashmir and more widely across India since at least the 1980s.

The precise extent of Pakistani government involvement in these attacks cannot be verified, but it is widely acknowledged that the notorious Pakistani Inter-Services-Intelligence (ISI) has been using Islamic fundamentalist groups to wage proxy wars. This began in the 1980s with the war in Afghanistan against the progressive Afghan government headed by Mohammad Najibullah, who had the support of the Soviet army to safeguard his administration, where the ISI was used by the US imperialists as their tool to manage the various reactionary Islamic groups which were deployed to Afghanistan to overthrow the then pro-Soviet government and subsequently to fight the Soviets. So, although the exact extent of the involvement of the ISI in the Pahalgam massacre is unclear, their usage of reactionary Islamic armed groups is well established.

Following the news of the massacre, the Modi government promptly used it as a pretext to cancel the 1960 Indus Water Treaty, a move that Modi has apparently long been considering.

The Indian government then launched ‘Operation Sindoor’ on May 7, targeting nine sites associated with the militant groups Jaish-e-Mohammed and Lashkar-e-Taiba in Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir. The BJP government claimed the strikes, involving missile attacks and Indian-Israeli developed SkyStriker loitering munitions (drones), ‘killed over 100 militants’ without targeting Pakistani military or civilian sites.

The Pakistani government countered by claiming that the strikes had caused 31 civilian deaths, including a child, alleging strikes hit civilian areas.

The conflict began to escalate rapidly. On May 7-8, Pakistan launched a mortar attack on Poonch, Jammu, killing one Indian soldier and 16 civilians, destroying homes, schools, and a Sikh temple. Pakistan claimed India struck three of its airbases, including the Noor Airbase near Islamabad, prompting retaliatory strikes by Pakistan as part of ‘Operation Bunyanun Marsoos’, targeting Indian airbases and a BrahMos missile storage site. India reported intercepting Pakistani drones and jets, with unconfirmed losses, including possibly a Rafale jet. Pakistan claimed to have shot down 77 Indian drones, while India reported neutralising Pakistani air defences, including a radar site.

As the dust settled on these encounters, it seems that the biggest winner, in terms of military reputation, is in fact China. This is because the Chinese J-10CE 5th generation fighters, operated by the Pakistani air force, shot down French supplied Rafale jets of the Indian air force, though the number of Indian losses in the air battle is still contested.

War in a multipolar world

A notable aspect of the Indo-Pakistan conflict is how the various allies of the two warring parties came into play. The Pakistani state has long been seen (correctly) as a willing tool of imperialism and its politically dominant military hierarchy, being closely aligned with imperialism (first British now US). Pakistan’s military hierarchy has shown itself willing to carry out coups against any leaders who tried to plot a more independent path for Pakistan, from Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto to Imran Khan. Consequently they have cleaved to the US imperialist bloc. This alignment with the US has led to revulsion on the part of the Pakistani masses, however, who flocked to support Imran Khan when he was ousted as prime minister and imprisoned after losing the support of the Pakistani army because he had tried to subject it to a small degree of civilian control.

The other tendency operating within the Pakistani state since 1959 has been an increasingly important economic and military alliance with China. This dates back, in fact, to the Sino-Soviet split, when Soviet Russia had closer ties to India. Pakistan has become part of the Belt & Road Initiative and the trade between the two countries has become increasingly important in recent years. This has coincided with an upturn in Balochi separatist activity in Pakistan as well as repeated attacks on Chinese workers involved in the projects being constructed in Pakistan.

India is a founder member of BRICS but is also subject to great efforts by the US imperialists to pull it firmly into a more aggressive anti-China stance in the hope that this will disrupt the further development of BRICS. The Indian bourgeoisie continues to balance between Russia on one side and the US on other. The Indian bourgeoisie profits greatly from reselling Russian oil, but has also joined ‘The Quad’, an anti-China military alliance consisting of the US, Australia, Japan and India. The international reaction to clashes between India and Pakistan has reflected this fragmented picture of international political alliances. What is certain though is that the imperialists have a shared interest in there continuing to be conflict between India and Pakistan as this increases tensions inside the BRICS system.

Kashmiris’ voice not heard

After the first war over Kashmir in 1947, the United Nations decreed that the future of the state should be decided by Kashmiris in a referendum. Almost 80 years later, this has still not taken place. The special autonomous status promised by the Indian government for Kashmir, in return for its ruler Maharaja Hari Singh acceding Kashmir to India, started being gradually eroded after 1953. This erosion fuelled hostility towards India, which in turn was met by further erosion, and even greater hostility until all autonomy was finally removed completely by the Modi government in 2019. Neither of the ruling classes concerned have any interest in allowing the self-determination of Kashmiris and both continue to claim to speak for them. The Indian government has been accused of a variety of abuses committed by their armed forces against the Kashmiri population and the armed groups backed by the Pakistani army have also been credibly accused of horrific acts such as mass rapes.

The way forward

Many believe that the Kashmir crisis would be solved were the people of Kashmir free to exercise self-determination, and even establish an independent state over all of the historic territory, but there is a wider problem at play here. Neither the Indian or Pakistani bourgeoisie are prepared to take the risk that they might lose out in any such process of self-determination.

Moreover for a small state such as Kashmir, with a population of around 17 million, (12.5 million of whom currently are Indian, with 4.5 million in Pakistan) to exercise independence (of either Pakistan or India) would be an impossibility in today’s political landscape. More likely than not it would end up being used as another occupation fortress from where the US forces would station themselves, all the better to interfere in the affairs of India, Pakistan, Nepal, Afghanistan, Central Asia and of course, Russia and China.

This points to a much wider problem: namely the contradictions and antagonism that have plagued both India and Pakistan since independence in August 1947.

India is now one of the largest economies in the world and yet 60% of the population of 1.3 billion live on $3.10 a day or less (the figure used by the World Bank to measure the prevalence of moderate poverty in developing countries). The contrast between the growing wealth of the Indian bourgeois and the vast proletarian and peasant masses living in poverty is one that neither the BJP or the Indian Congress has shown any ability or will to resolve. Both parties are committed to free market economics and are firmly the vehicles of the wealthy ruling bourgeois and landed classes.

In Pakistan the situation is similar with 42.5% of the population living below the poverty line according to the World Bank. Pakistan is also paying the price for the ruling military clique’s long-term collaboration with imperialism, with even Pakistan Defence Minister Khawaja Asif recently commenting that being allied with the US had done great damage to the country.

The Kashmiri crisis provides deeply cynical bourgeois politicians in both countries with a means of drumming up nationalistic and communal hatreds to distract from growing domestic problems. This might be why Modi has been declaring that the war has not ended yet, despite a truce being declared by May 10th in the latest round of clashes. For Pakistan, only by ending the collaboration with US/British imperialism can the country truly achieve independence and sovereignty. For India, the attempt at playing both on the side of BRICS and US imperialism presents no positive way forward in the medium to long term. US imperialism does not look at India as a ‘partner’ because the imperialists have no ‘partners’ but only subservient stooges who do the bidding of the US.

The continued animosity between the two great states over Kashmir is a legacy of the wretched ‘gifts’ of the British empire for both countries (just as was the Indo-Chinese war of 1962 and the War between East and West Pakistan in 1971, or the long-lasting Sri Lankan conflict between the Tamil and Sinhalese populations), compounded by the policies of the Indian and Pakistani bourgeoisie.

It is vital that this wound be healed, and the only way this can be done, in the immediate term, is for the Indian government to start by honouring the commitment made when Kashmir originally acceded to India and to re-establish Kashmir’s special status within India in a meaningful way. This alone will not of course stop Pakistan’s claims to entitlement to rule Kashmir as a Muslim majority area, attempts which are bound to gain sympathy within Indian Kashmir so long as the Indian government persists in its anti-Muslim activity throughout India. Given the damage that their mutual enmity is causing to both India and Pakistan, their best way forward would be to negotiate a treaty of friendship and cooperation in the light of their joint membership of BRICS. If there are strong forces in both countries hostile to such a move, there are also forces there who would very much favour it, and those forces have the real interests of the masses of both countries on their side.

As we have argued throughout this article, though, the status of Kashmir is but one aspect of a much broader problem and that is the lingering effects of Partition and the almost eighty-year state of war and near-war that has existed between India and Pakistan, as well as the ongoing cancer of communalism that persistently and periodically flares up in both countries.

The chief beneficiaries of this division are the imperialists and the most reactionary, ruling-class elements in both India and Pakistan. Ending the ongoing dispute over Kashmir would remove one barrier to cooperation between the two countries that could lead to further mutual economic development which would help to strengthen the progressive social forces in both countries.

Ultimately, of course, the enormous human, cultural and economic potential of India and Pakistan will only be realised through the removal of the reactionary bourgeois ruling classes in both countries and the building of socialism across the Indian subcontinent. Only through the coming to power of the proletariat and peasantry can the damage done by imperialism be fully undone and the gigantic human potential of the subcontinent, and of its talented and creative peoples, break free of the bonds of reaction.