Planning reforms don’t address housing shortage

Building more homes is not the answer unless they are built for those that need them.

Building more homes is not the answer unless they are built for those that need them.

Amid the Covid pandemic, and as the first lockdown was opening up, the government announced a ‘once in a generation’ shake-up of England’s planning system. On 6 August 2020, the government published the White Paper ‘Planning for the Future’ which proposes significant changes to the current planning system.

These changes are presented as a solution to the lack of housing provision across the country and the need to construct 300,000 homes a year as part of the government’s ‘Build, build, build’ agenda.

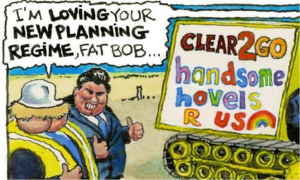

The blame for the lack of housing is laid by government squarely at the planning system which is accused of slowing down the process of development, resulting in the housing shortage. As prime minister Boris Johnson put it when announcing the reforms: “Thanks to our planning system, we have nowhere near enough homes in the right places.”

These changes put simply are a raft of reforms that in effect de-regularise the planning system, simplifying it and removing so-called red tape to ‘enable’ development. In short, they remove from the planning system a significant amount of the planning element.

Rather than set requirements, standards and parameters to be adhered to, and incorporate levels of scrutiny of individual applications for development through the process, there is to be a broad plan for an authority showing areas that can be developed and areas that shouldn’t be developed and let the market do the rest. It is obvious to most of us that, with the market at the helm, the results of such proposals are not going to be affordable, grand design, leafy streets and spacious abodes for one and all.

The Planning White Paper

The reforms outlined in the planning White Paper make some significant changes to the role of local plans and land use allocations. Currently we have a system where local plans are drawn up by authorities that allocate uses to land that future development has to adhere to in seeking planning permission. The production process for local plans is notoriously long winded but does involve a level of public consultation and scrutiny and covers a 10 or 15 year period. Most proposed development will require a planning approval from the authority which involves a further round of consultation, both with the public and expert bodies.

The planning White Paper proposes to get Councils to zone all land in their areas within one of three categories: ‘growth’, ‘renewal’ and ‘protected’, which will determine the level of planning permission needed. In ‘growth’ areas, planning permission would be granted automatically to new homes, shops, offices, hospitals and schools. In ‘renewal’ areas, development would be given ‘permission in principle’ subject to basic checks, and in ‘protected’ areas, e.g., green belt, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty etc., development would require a full planning application process to obtain permission.

The result of the proposed new zoning system is a greater element of market forces unleashed on the sector, with less scrutiny through consultation and a quicker route to rubber stamping development. This may well speed up potential development but it also increases the likelihood of creating “concrete deserts” that are “devoid of green space”, as Hilary McGrady, the director of the National Trust, has warned.

Housing algorithm backlash

No sooner had Boris Johnson announced the big planning shake-up than his Housing Secretary, Robert Jenrick, was facing a backlash from none other than the Tory back benches.

This was not because they were concerned with the lack of control and protection of good design and amenities that the reforms may introduce. No, it was a classic case of NIMBYism. The ‘Not In My Back Yard’ approach to planning. Their opposition, one of the most vocal being former Prime Minster Theresa May, was to an algorithm, a central part of the reforms, that allocated new housing quotas across the country to meet the 300,000 homes per year target.

Furthermore, The Times tells us that “Boris Johnson has been accused of hypocrisy after he objected to a scheme for 514 homes in his constituency claiming it was ‘inappropriate’ and ‘out of character’ for the area.

“In letters obtained by The Times through a Freedom of Information request, Mr Johnson said that the plans for houses in his Uxbridge & South Ruislip seat constituted ‘overdevelopment’”.

However, Robert Jenrick, the housing secretary, has ridden to the rescue of his prime minister and “has intervened in the case and is blocking planning permission from being granted to the scheme, which includes 179 affordable homes”.

It would never do to upset Boris Johnson’s NIMBY constituents, as after all “Mr Johnson’s majority of 7,210 in his west London constituency is the smallest of any prime minister in recent times” (George Grylls, ‘”Build, build” Johnson opposed new homes in his constituency’, 14 December 2020).

As was pointed out by several commentators, one would have thought the government had had enough of algorithms after the debacle of the exam-grading in the summer. Indeed, when questioned about the housing algorithm, the prime minister joked: “Algorithms are banned”.

The housing algorithm was at the heart of these planning reforms, as Johnson’s original comment in announcing them stressed “we have nowhere near enough homes in the right places.” The algorithm was designed to address just this point. It was designed to ensure not only that the government would meet its target of building 300,000 new homes a year but that they were built where housing pressures are greatest. It identified where housing demand was greatest based on the affordability of existing homes in an area and how this had changed over the past decade.

It should have been no surprise that the areas with the highest targets were the affluent suburbs in the southeast, which, as part of the original algorithm, increased the target for the region by 57 per cent, to 61,000 and increased that of the Southwest region by 41 per cent, while it reduced the targets for regions in the Midlands and the North.

Cue the uproar from the Tory backbenches and the very prompt about-turn by Mr Jenrick in the method for calculating the housing targets that the planning White Paper will be centred around.

The change to the algorithm has been couched in the jargon that it is part of the government’s “desire to build homes on brownfield sites” and “in our great cities and urban centres”.

The new algorithm now requires the 20 biggest cities to provide up to 35 per cent more housing than previously imposed. Or as Simon Nixon in The Times pointed out: “the algorithm is therefore to be revised so that it gives a more palatable answer. Instead of building the new homes where people want to live, they will now be built where Tory MPs think they should live. That is in urban areas, preferably in the North. You could call it levelling up” (‘Housing algorithm was doomed but planning system must be reformed’, 17 December 2020).

Does more development equal more housing?

“Build, build build” is Boris’s latest mantra. The bigger questions are what is being built and for whom. While the planning reforms have the potential to speed up the build process, they do nothing to address those questions.

In fact, over the past decade the numbers of new homes being built has been rising, yet so too have house prices, while wages have not. The result is that, although there is more housing stock, home ownership is unaffordable for many.

Yet with more houses being unaffordable, the route of providing ‘affordable housing’, those sold or rented below the market rate, has also come under question as part of the current planning reforms.

Currently about half of all ‘affordable housing’ is provided by developers through Section 106 contributions agreed with the local authorities. The planning White Paper proposes scrapping Section 106 and replacing it with a flat rate Infrastructure Levy. It is claimed that the levy will contribute as much if not more affordable housing as the current system, yet there is very little detail within the White Paper to back that up, and a lot of well-founded scepticism that the result will be less housing designated as ‘affordable’.

Social housing continues to be under the cosh

As has been seen, the planning White Paper shows no attempt at addressing the housing crisis within the private sector and, unsurprisingly, neither does it do anything to address the crisis within social housing. In fact, the planning paper does not mention social housing, the replacement for council housing on which people on low incomes rely. Council housing was once a significant part of the housing supply and yet over the last 50 years the construction of new social housing has reduced significantly.

“Between 1980 and 1984 local authorities built 220,000 new homes, a quarter of the total built. In the last five years they have contributed just 10,000 — roughly 1 per cent of total new supply. The number of homes built by housing associations has increased but not enough to fill the gap left by councils….

“Rhys Moore, an executive director at the National Housing Federation (which represents housing associations), has warned that ‘simply building more homes would not help the 8.4m people currently hit by the housing crisis in this country . . . Instead, we desperately need more social housing that people on lower incomes can afford — and there are many unanswered questions about what effect the proposed reforms will have here’” (George Hammond, ‘England planning shake-up provides few affordable housing guarantees’, Financial Times, 3 September 2020).

The planning White Paper sets the target of 300,000 new homes that chimes with the fact that there is a housing crisis with people in need of homes. What it fails to do is guarantee that any of those 300,000 homes would be for the very people in need of them. The reforms continue to push open the door for private developers to build with fewer controls, standards and requirements. Build, build, building is not going to address the country’s housing crisis; instead it will result in more bricks and mortar standing empty as those that need them are priced out of living in them.

Existing housing stock in question

The ongoing Grenfell Inquiry continues to expose how the building industry operates and is bringing into question the safety of thousands of existing buildings across the country.

Previously we covered how the first phase of the inquiry confirmed that the type of cladding, aluminium composite material (ACM) used at Grenfell was responsible for the rapid fire spread that led to 72 people losing their lives in 2017 and hundreds to be still suffering from the consequences of the tower’s tragic fire.

The latest exposure of the combustibility of the insulation that was used on the refurbishment of Grenfell has pushed more flats into the danger zone. The scandal of the Kingspan insulation was highlighted by the flagrant language within some of the emails of one of the technical directors dealing with questions of their products and fire safety.

Philip Heath, former technical manager, received a question in 2008 from an employee of Bowmer & Kirkland, who wrote: “To date you have not substantiated on what basis K15 is suitable for buildings over 18m.” Mr Heath forwarded the message to colleagues with the comment: “I think Bowmer & Kirkland [multinational blue chip main contractor] are getting me confused with someone who gives a dam [sic]. I’m trying to think of a way out of this one, imagine a fire running up this tower!!!”

In another string of emails, Mr Heath told a fellow employee that a façade engineering firm, Wintech, who were questioning the suitability of the product and digging their heels in on a couple of projects, that “Wintech can go f*** themselves and if they’re not careful we’ll sue the arse off them” (Sean O’Neill, ‘Grenfell insulation firm manager “sneered at customers’ safety fears”, inquiry told’, The Times, 1 December 2020).

Mr Heath’s attitude to the questions is indicative of the attitude of the industry to fire safety. While he can be singled out, he is a product of the way business operates: since maximum profit must be made, there is no space, time and mostly money for considering people or safety.

The company had falsely claimed its product was suitable for use in high-rise buildings by obtaining official test results using different materials to those actually used in the sold product. In more damning internal communication, text messages between members of Kingspan’s technical team, Peter Moss and Arron Chalmers, the year before the Grenfell conflagration joked about the way the firm had managed to get its Kooltherm K15 insulation categorised as ‘class 0’ — that is, appropriate for use in buildings higher than 18 metres — in part by using a different material in the official tests from what was actually being sold. Chalmers: “Doesn’t actually get class 0 when we test the whole product tho. LOL.” Moss: “WHAT. We lied? Honest opinion now.” Chalmers: “Yeahhhh …”, and later in the conversation, “All lies, mate … Alls we do is lie here” (quoted by Dominic Lawson in ‘Grenfell is becoming our worst corporate scandal’, The Sunday Times, 13 December 2020).

The Sunday Times has reported that, following the exposure of the combustibility of ACM cladding, 30,000 flats were identified as having combustible cladding, with 700,000 people still living in high-rise flats with this dangerous cladding. Now the inquiry “has exposed a further 186,000 private high-rise flats wrapped in other flammable materials. Next it could leave up to 1.5 million modern flats, 6 percent of England’s homes, unmortgageable because they cannot prove their walls are safe, breaking the first rung of the property ladder” (Martina Lees, ‘Thousands of families trapped as “unsafe” flats paralyse property market’, The Sunday Times, 20 September 2020).

Up to four million people now live in unsafe houses, with exorbitant insurance and waking watch bills pushing many into serious financial difficulty. The government has allocated £1.6bn in grant funding, yet MPs on the housing select committee found repairs could cost £15bn. The bill for the rest is going to fall at the feet of homeowners and leaseholders.

The government’s answer for that is to consider providing long-term loans, a loan for £30,000 to fix a typical mix of risky cladding. Missing fire stops and flammable balconies would add about £1,500 a year to household bills at a 3% interest rate. Yet no compensation is being sought from those responsible for building the death traps. The five biggest housebuilders, all with developments where fire risks have rendered unsaleable homes they built and sold, have made pre-tax profits of almost £10bn since the lethal Grenfell fire (not including Persimmon’s results for their current tax year, which will increase the total). (See Martina Lees, ‘Government’s solution to cladding scandal: just take out a second loan’, Sunday Times, 6 December 2020).

The corporate supply chain is also left off the hook. And to add insult to injury, the founder of Kingspan, Eugene Murtagh and his son Gene, who is now in charge of the company, cashed in shares worth £98 million in the weeks before the inquiry got into the question of Kingspan’s insulation testing, certification and supply.

The ones that have been creaming all the profits are the very ones in least danger of footing any of the cost of remediating their failures.