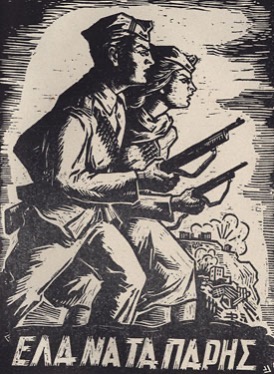

How British Imperialism Crushed the Greek Revolution – Part 2

(By Nina Kosta and George Korkovelos)

The British in Greece

English historian Elizabeth Barker writes that during WW2, the British government “continued to behave as if Greece was its fiefdom“. The only military aid that Britain gave to Greece was Italian loot from North Africa, while at the same time undermining efforts to buy modern aircraft from the US, which eventually, although paid for by Greece, ended up in the RAF.

The British presence in occupied Greece was a brutal colonial operation that led to the Greek Civil War (1946-1949). Churchill considered Greece to be an integral part of the British Empire and wanted exclusive control over it:

“Even the last British employee controlled the Greek government abroad (exiled in Cairo) completely. They controlled, almost completely, all the resistance organizations inside Greece. Except for EAM, with which they were obliged to discuss and negotiate“, writes Phoebos Grigoriadis, chief of staff of ELAS (Greek People’s Liberation Army) in the Attica-Boeotia region, in his book Resistance.

The British officially kept more than 150 officers in the Greek mountains – a number outrageously greater than their war needed, but absolutely necessary for their ultimate aspirations. It is estimated that in Greek territory British secret agents were numerous, and more than 5,000 Greeks had some connection with the various English secret services.

The anglophile General Secretary of the Union for People’s Democracy (ELD) and co-leader of the National Liberation Front (EAM), Elias Tsirimokos, describes the English who were in the Greek mountains:

“Most of them had common characteristics. Young, brave, healthy, sportsmen, sharp as a needle, with sincere contempt for the people and pure hatred for the idea of social change. They parachuted in our mountains with the will to serve their homeland and with the taste of adventure. Left alone on their own initiative, they had all the appetite to do something, not only brave actions, but also their first steps in imperial politics. […] And here they were, in a small, backward place, representatives of a Great Power […] they probably acquired the mentality of the children of very rich or very strong parents who are left to do whatever comes to their mind, knowing that they have ‘their backs‘. […] They could not approach, feel and love the proud people who fought for their country, but they had not learned, nor did they want to learn, to flatter foreigners. On the contrary, every such person was very willing to be considered an ‘enemy of England’ ” (published in the newspaper Acropolis, 21 January 1973).

Ordinary Greeks in the countryside saw the English as saviours. They opened their homes and their hearts. The head of the British Military Mission, Brigadier General Eddie Myers, describes his tours in the countryside and the warmth of the Greeks:

“I could have ended up in the house of one of the poorest Greeks, who, no matter how poor he was, always behaved with the greatest generosity and the highest spirit of hospitality. […] They always gave us not only the best they had, but also gave from the little they had. It could seem pointless to an Englishman, but it showed the quality of these Greek mountaineers“.

Myers, despite the subsequent compliments for the Greeks, during the Occupation at least, hated them. “I do not trust any Greek,” he said, considering all the inhabitants of this country ‘Asians’and most Asian of all Aris. (Referring to Aris Velouchiotis, the leader of ELAS).

Most of his officers had the same feelings. One of them, calls the Greeks “the hairy monkeys that infect this country“, writes the historian R Clogg.

What must be emphasised is that the British officers, both during their period of action in the Greek mountains, and after the liberation, in their books and interviews, “judged the Greeks in accordance with the aims of British policy” (O Smith). No person, no organisation, no event is presented positively if it does not identify with their policy.

“In Greece, the testimonies of British officers against EAM/ELAS were exploited for political reasons. These testimonies were a valuable help to the post-war governments, in the context of their attempt to falsify Greek history. Now we can happily put things in their place” (O Smith, from the Proceedings of the Conference Greece 1936-1944).

To those who willingly obey their orders, the British were a little more tolerant, without ceasing to underestimate and ridicule them.

The best moment between EAM and the British was when the subordination of ELAS to the Middle East Headquarters was signed. Mentioning even the name ‘ELAS’ was banned in Cairo by English censorship, writes the poet and diplomat Giorgos Seferis in his Diary.

How ‘their’ imperialist history is written:

The abduction of the German Lieutenant General Kreipe in Crete was widely publicised because it was carried out by the English officer Patrick Lee Fermor and thus became legendary.

Coincidentally, on the exact same day in the Peloponnese, the permanent lieutenant Manolis Stathakis, with ELAS guerrillas, ambushed and killed the German Lieutenant General Krech but the fact was silenced and no one mentions this important success for all the Balkans.

Likewise, the great battle of ELAS against superior German forces in Karoutes on August 5, 1944, was led by Colonel Rigos. US Officer Ford and British Officer Joe were watching, raising serious doubts about whether the partisans would be able to stop the iron-clad Hitlerites. The Greek colonel interrupted them: “No one will escape“. In a little while, the American excitedly threw his hat in the air during the successive phases of the battle and constantly repeated: “Tomorrow you will hear how much Cairo will broadcast about the battle“. The Greek colonel stopped him again: “They will not say anything“. And indeed, they did not.

As Christopher Montague Woodhouse, successor of Eddie Myers as head of the British military mission in Greece and faithful servant of imperialism, later admitted, “The BBC had orders to mention only Zervas – head of EDES, the British sponsored resistance.“

The subversive activity of the British officers against the National Liberation Front (EAM) movement is reflected in a confidential report of Brigadier General Myers, who wrote the following – for the first report to his superiors – two days after his arrival in Cairo:

“X – 12 August 1943, Strictly Confidential (85-4 A.S.)

“According to your latest instructions, I have instructed the British and Greek agents working under my administration to torpedo the work of ELAS and EAM and to prevent them from stabilising their position and gaining a dominant influence in Greece. However, such an outcome is problematic as the monarchists have no political influence in the country and their leaders are hated by the Greek people. […] On the contrary, the political and military organisation of EDES is making remarkable progress, especially in Epirus. It is imperative that it be given war materiel and that we strengthen it morally. In my opinion, this organisation will be useful to us, on the one hand as a counterbalance to ELAS and on the other hand, when it (EDES) has been strengthened, it will possibly be able to be used against it (ELAS). One day it will be necessary to disband ELAS. […] I have the impression that it would be useful for our agents to get in touch with the representatives of the Government (the collaborationist state) in order to encourage in them the idea that they have the duty and the right to hand over the leaders of EAM and ELAS to the occupation authorities and to assist in the capture of their agents to such an extent that these organisations, when the time comes, will be unable to oppose British interests.

“In this field, EDES helped us, it already handed over to Colonel Dertilis and Minister Tavoularis many personalities of the EAM, who are now in the hands of the Germans. […]

“I think it would be better to delay the liberation of Greece for six months or a year than to allow it to fall under the rule of EAM” (Report published for the first time in October 1945 in the Bulletin of the Hellenic-American Association of the USA and subsequently in 1967 in the book by the French historian Jacques de Launay Major Controversies of Contemporary History).

In 1978, Brigadier General Myers, questioned about this particular document at a conference entitled Greece 1936-1944, claimed to have been unaware of its existence. Whether he told the truth or not, there has been no other text in which British politics in practice is so clearly captured.

Along the same lines with Myers, Colonel Tom Barnes writes: “I believe the best solution is for Greece to become a British protectorate for ten to twenty years after the war.”

An American report mentions these plans, which still remain buried along with a wealth of other information in British classifieds:

“At that time a small group of capable officers tried to divert attention to the need to encircle and, if necessary, imprison the communist commissars and captains who ruled the ELAS administration” (F Spencer, ‘War and Post-war Greece’, from the book by Andreas Kedros The Greek Resistance 1940-’44).

The British were discussing a plan to gather an English brigade in the mountains for the capture of the General Staff and the violent dissolution of ELAS. For EAM, a popular mass movement, to be out of their control was clearly not tolerable to the British who took the view that when the time came, it would either have to surrender or be dissolved by force. That is why, after April 1943 the British authorities proceeded to prepare the head of the British military mission to Greece for what was to follow:

“The Cairo authorities consider that after the liberation of Greece, a civil war is almost inevitable” (Myers). And this is exactly what happened.

The defeat of ELAS

In May 1944 it had been roughly agreed in the Lebanon Conference that all non-collaborationist factions would participate in a Government of National Unity. Eventually 6 out of 24 ministers were appointed by EAM. Additionally, a few weeks before the withdrawal of the German troops in October 1944, it had been reaffirmed in the Caserta Agreement that all collaborationist forces would be tried and punished accordingly; and that all resistance forces would participate in the formation of the new Greek Army under the command of the British.

When the British entered Athens in mid-October 1944, things were so contradictory in the recruitment and operation of the guerrillas that, while they could have come down and occupied strategic positions, they did not do so and essentially left Athens and Piraeus unfortified in the hands of the British and their colonial troops.

No fighting took place when they first landed at Skaramagas, Keratsini and then Faliro. Without any battle, they were instead greeted by the ELASites and their reserve and the EAM, chanting “The Allies came”, waving British, American and Soviet flags together and holding laurels. The British did not fight, they simply came in and the Greeks welcomed them. Yet, on 1 December, the British commander Ronald Scobie ordered the unilateral disarmament of EAM-ELAS. The EAM ministers resigned on 2 December and EAM called for a rally in central Athens on the 3rd, requesting the immediate punishment of the collaborationist Security Battalions and the withdrawal of the “Scobie order“. The rally of some 200,000 people was shot at by the Greek police and gendarmerie, leaving 28 protesters dead and 148 wounded. These killings ushered in a full-blown armed confrontation between EAM and the government forces at first (which included the Security Battalions), and during the second half of December, between EAM and the British military forces.

The British entered Athens without resistance and even the guerrilla forces in the nearby mountain of Parnitha did not come down. ELAS was very wrongly given instructions to turn to a fight against Zervas in Epirus. When in fact ELAS could hold Athens in their hands, they were told to turn away. Only when there was an attempt by the British to enter the National Road to go to the Peloponnese did ELAS attack them and the British had to change their mind. However, inside Athens, British snipers used the Acropolis as a fortress and ELAS would not shoot against them out of respect for the monument, even if the shameful attitude of the British respected nothing. The 33 days of fierce clashes and sacrifices known as The Dekemvriana (The December events) are the climax of class struggle between the Greek people and the British-backed bourgeoisie and its collaborationist machinery. This period and its lessons will be the subject of another article in the very near future.

The Soviets had contractual obligations towards the British, and ELAS was perceived as part of the Red Army. It was impossible to be six months away from ending the war and have another war between the components of the allied front on a strategically important spot of the Balkans. These were very difficult and extremely unlucky circumstances for the revolutionary movement in Greece. In the existing historical research, even by the Greek Communist Party in its most honest phases, not enough emphasis is given to factors such as the timing when these events took place, the potential they had, and what correlations of power existed.

The fallacy of blaming Stalin for every failed revolution

In the following extract that comes from his book The essential Stalin, Bruce Franklin offers a clear answer to unfounded accusations:

“Stalin’s role in the Spanish Civil War likewise comes under fire from the ‘left.’ Again taking their cue from Trotsky and such professional anti-Communist ideologues as George Orwell, many ‘socialists’ claim that Stalin sold out the Loyalists. A similar criticism is made about Stalin’s policies in relation to the Greek partisans in the late 1940s, which we will discuss later. According to these ‘left’ criticisms, Stalin didn’t ‘care’ about either of these struggles, because of his preoccupation with internal development and ‘Great Russian power.’ The simple fact of the matter is that in both cases Stalin was the only national leader anyplace in the world to support the popular forces, and he did this in the face of stubborn opposition within his own camp and the dangers of military attack from the leading aggressive powers in the world (Germany and Italy in the late 1930s, the US ten years later).

“After the showdown against the popular forces occurred in Greece we meet another ‘left’ criticism of Stalin, similar to that made about his role in Spain but even further removed from the facts of the matter. As in the rest of Eastern Europe and the Balkans, the Communists had led and armed the heroic Greek underground and partisan fighters. In 1944 the British sent an expeditionary force commanded by General Scobie to land in Greece, ostensibly to aid in the disarming of the defeated German and Italian troops. As unsuspecting as the comrades in Vietnam and Korea who were to be likewise ‘assisted’, the Greek partisans were slaughtered by their British allies who used tanks and planes in an all-out offensive, which ended in February 1945 with the establishment of a right-wing dictatorship under a restored monarchy. The British even rearmed and used the defeated Nazi ‘Security Battalions.’ After partially recovering from this treachery, the partisan forces rebuilt their guerrilla apparatus and prepared to resist the combined forces of Greek fascism and Anglo-American imperialism. By late 1948 full-scale civil war raged, with the right-wing forces backed up by the intervention of US planes, artillery, and troops. The Greek resistance had its back broken by another betrayal not at all by Stalin but by Tito, who closed the Yugoslav borders to the Soviet military supplies that were already hard put to reach the landlocked popular forces. This was one of the two main reasons why Stalin, together with the Chinese, led the successful fight to have the Yugoslav ‘Communist’ Party officially thrown out of the international Communist movement. Stalin understood very early the danger to the world revolution posed by Tito’s ideology, which served as a Trojan horse for US Imperialism”.

Testimony of an anti-revisionist Greek fighter

Giorgos Gousias (1915-1979) was a member of the Politburo of the KKE, a key collaborator of its General Secretary Nikos Zachariadis during the revolutionary period. We are translating here his first hand historical account published in his book The reasons for the defeats and the split of the KKE and the Greek Left.

Gousias writes about how Stalin agreed that the reason for the defeat of the Greeks (in 1949) was the unsolved problem of reserves, the unresolved issue of supply of the units in southern Greece, the open betrayal of Tito, and the enormous support that the Anglo-Americans gave to the local reaction. Gousias recalls that Stalin said “well done” to the Greek communists who had had to retreat, as they could not continue the war after the situation that was created in the Balkans and that he agreed on the new tasks that were facing the movement in Greece.

Gousias refers extensively to a meeting between Stalin and the leadership of KKE, where Stalin answered a question on rumours that Tito and his associates were spreading. Rumours were spread that in a meeting Stalin had had with the Yugoslavs, he allegedly told them that he did not agree with the armed struggle of the Greek communists and that he asked them why they were patronising it. Zachariadis then asked Stalin why he did not help ELAS. Stalin replied that he could not do it because the Soviets would be in conflict with the British and they did not have a navy to carry out such an action. Gousias writes that Stalin considered it a mistake of ELAS that it did not fight the British (right from the start), and he considered it a mistake that after the loss of Athens, ELAS did not continue to fight and much more that it reached the point of voluntarily surrendering its weapons.

In that meeting, Zachariadis told Stalin that he knew of the existence of a letter by Georgi Dimitrov, then head of the foreign department of the Central Committee of the CPSU, which was sent to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Greece when the battle was taking place in Athens in December 1944, suggesting stopping the battle because the situation did not allow for the Soviet Union and the People’s Republics to offer assistance. Stalin replied to Zachariadis that Dimitrov could not speak for the Central Committee of the CPSU. Zachariadis (who only returned to Greece from the Dachau concentration camp in May 1945) had received a notification from Dimitrov that a leading member of the KKE (Siantos) was an agent of the British. The discussion with Stalin reinforced the view of Zachariadis that the struggle against the Hitlerite-fascist occupation had been betrayed by people like Siantos.

Gousias writes about how Zachariadis and Stalin and other members of the Soviet leadership discussed the deployment of the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) fighters and the civilian population. It was decided that all the people who had retreated to Albania would be taken by the Soviets by boat and stationed in the capital of Uzbekistan, Tashkent. The others who entered Bulgaria would be sent to various People’s Republics. Stalin ordered the ships to be ready immediately and the transport to begin in October-November 1949.

Zachariadis thanked Stalin and the other members of the CPSU leadership for this gesture. Stalin said to Zachariadis: “You have nothing to thank us for, you did a lot for us while we could not help you, but we reserve the right to do so.”

With the document signed by Stalin and the decisions they made about the refugees, and after all the discussions they had to clear up a number of issues, Zachariadis left the Soviet Union and returned to Albania.

As soon as Zachariadis returned, the Politburo of the KKE met and gave the document, that was written in Russian and signed by Stalin, to other members to read. Gousias writes that they were all satisfied with the discussion:

“With understanding we saw everything that Stalin said about the difficulties that were presented and our fight that was not helped. And we felt satisfied, because there was a common perception about the causes of our defeat and about the new tasks that now came before us. We decided to convene the 6th plenary session of the KKE Central Committee”.

In October 1949, the 6th plenary session of the KKE’s Central Committee took place in Bureli, Albania. Petrov and the delegation of the Central Committee of the Albanian Labour Party, headed by Mehmet Sehu, took part in its work on behalf of the CPSU. Gousias writes about the discussion which took place and the decision which was made unanimously and published as ‘The new situation and our duties‘. It read as follows:

“1. Our confrontation in 1949 in Vitsi and Grammos was one of the toughest battles (napalm bombs were used for the first time against Communists). The fighters and the cadres of the Democratic Army fought well, but faced with the enormous superiority of the opponent we were defeated. The tactic of continuing the war definitely expresses a petty-bourgeois spirit of despair, which is why the political bureau of the KKE Central Committee acted correctly, following the tactic of retreating, which prevented the opponent from annihilating the main force of the Democratic Army.

“2. With the battle of Vitsi-Grammos, an important phase in the post-war course of the popular movement of our country closed. The following conclusions were drawn: (a) In December 1944 the KKE organised the heroic resistance of our people, against the English intervention. ELAS, however, due to a series of opportunistic mistakes in the period of Hitler’s occupation, was in many respects unprepared to face victoriously the intrigue of English imperialism. (b) The persistence of the KKE and the EAM after Varkiza, for a smooth democratic development had been exhausted. The broad popular strata were convinced that there was no other way out of the armed struggle imposed on the people by the foreign and local reaction. At the same time, this policy of the KKE and the EAM prevented British imperialism from intervening militarily. (c) The time for the start of the armed struggle was appropriate. Internally, this need became consciousness for the broad masses. Externally we relied on the People’s Republics, we had not yet Tito’s apostasy and the balance of power on a global scale had changed in favour of democracy and socialism. The KKE, organising and leading the new armed struggle, drew the right line for the creation of the people’s army with the aim of overthrowing the local reaction. A correct combination tactic of the regular army war and the guerrilla warfare was elaborated. (e) The 5th plenary session, based on a correct analysis of the situation that prevailed in 1948 and early 1949, declared that we can win the turning point in our internal development. The Democratic Army, despite the fact that it could not solve its main problem of the reserves, came out of the test of 1948 stronger. The international situation was generally favourable for the camp of democracy – hence the promise we received in the autumn of 1948 from the leadership of the CPSU for help in military means and other supplies. (f) the outcome of this year’s confrontation with the local reaction, determined the fact that the party, in conditions where the difficulties for our struggle grew mainly due to the betrayal of Tito and its exploitation by the Americans, their increased insistence to keep the bridgehead in Greece, greater support for monarcho-fascism, etc., could not solve the basic problem of the reserves of the Democratic Army and the supply of its units in Central and Southern Greece, failed to break the situation created by monarcho-fascism in Greece and combine a strong mass movement in the cities with the war of the Democratic Army.

“3. The 6th plenary session, based on the new situation, summarised the following events:

“Stop the armed struggle. Transfer of the centre of gravity of the work of the KKE to the organisation and guidance of the political struggles of all strata of the working people. ‘Based on the programme for the democratisation of Greece, it is necessary to unite all the progressive forces of the country, in a common front fighting for the issues of the people, demobilisation, independence and peace’ ”.

Gousias writes that the Communists were forced into a temporary retreat. However, the three-year heroic epic of the Democratic Army of Greece was an invaluable asset of the revolutionary movement. Gousias makes a strong point that as the Greeks retreated, a world-historic event took place, the second in a row after the October Revolution, the victory of China’s popular forces, and the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China. The Communist Party of China had called the struggle of the Democratic Army of Greece “the second front of the Chinese war”.

Gousias’ account, that is full of historical accuracy and Marxist objectivity, is in stark contrast with the phenomenon of liberal tears over the defeated Greek Revolution and the Greek partisans who were allegedly “abandoned to the fascists by the Allies both capitalist and Soviet“. One needs to consider a few important points that Australian anti-imperialist activist Jay Tharappel makes in order to counter such liberal hypocrisy and lies.

“Even if Greece succeeded in becoming a socialist country, most of these liberals would probably denounce it as ‘Stalinist’ given that the KKE of the time would effectively have been in charge, so why do they pretend they care? Some seem to like communist victims, especially if their victimhood can be blamed on Stalin, but once they take power they become evil Stalinists.

“The USSR already lost 27 million people in WW2, if you don’t have to deal with the consequences of sending the Red Army to Greece to help ELAS (Greek resistance) against the fascists, then you’re in no moral position to judge. The Red Army was not full of Stalin’s personal robots; they were conscripts with families who had already been through hell.

“The mistake lies with ELAS (not the USSR) for handing over their weapons in the Varkiza agreement at a time when they had four-fifths of Greece under their control, and then agreeing to the British proposal to arrive with their troops on the promise that elections would follow, which never came because the British handed the weapons of the resistance over to the fascists.

“Liberals forget that ‘Nazi terror’ did not just ‘come to an end’ but was defeated by the Soviet Union, for whose sacrifices we will be indebted for life. Instead of gratitude, some prefer to spit on the liberation of Europe by complaining about Stalinism like the liberal hypocrites they are.

“No, the Greek partisans were not ‘abandoned to the fascists’ by the Allies, the Allies re-armed the fascists to fight the partisans. Talking about Stalin ‘abandoning the partisans’ means letting British imperialism off the hook.’’

Also another thing that we need to counter is any notion that the British Labour party was proposing anything different than the policy of Churchill.

With the electoral victory of Labour in London, the movement in Greece was encouraged and the right wingers were terrified. However, it soon became clear that the Labour Party, for all its pre-election pounding on Churchill for his policy during the December incidents, was determined to continue on the same bloody path until every progressive citizen in Greece was exterminated. They compiled the report of Sir Walter Citrine, the trade union leader of the British TUC (Trade Union Congress), who rushed to Athens in search of mass graves. The war of impressions was put into practice, the counting of corpses (cadaverology), which is after all a constant tactic of imperialism (as we can see from the recent example of the massacre in Bucha, Ukraine) and it aimed to present EAM, ELAS, OPLA (Organisation for the Protection of the People’s Struggle) and the KKE as criminal organisations. The crews of Citrine were digging up civilian victims of the bombings, and their provocations reached the point of presenting the victims of December, in shared graves throughout Attica, mixed with bodies of the security forces and guerrillas, horribly deformed. The aim was to attribute all the dead, both perpetrators and victims, fighters and anonymous alike to “the communist butchers”. The movement in Greece responded to this defamation campaign by the deeply anti-communist lackey of Labour and its trade unionists, with the publication of the pamphlet entitled The Hellenic Katyn where the Goebbelsian propaganda is debunked.

Agents of colonial barbarism

It is significant to note that the man in command of the British Police Mission to Greece was Sir Charles Wickham, who had been assigned by Churchill to oversee the new Greek security forces – in effect, to recruit collaborators. He was one of the persons who traversed the empire establishing the infrastructure needed for its survival. He established one of the most vicious camps, in which prisoners were tortured and murdered, at Gyaros.

He had served in the Boer War, during which concentration camps in the modern sense were invented by the British. He then fought in Russia, as part of the allied force sent in 1918 to aid White Russian czarist forces in opposition to the Bolshevik Revolution. After Greece, he moved on in 1948 to Palestine. But his qualification for Greece was this: Sir Charles was the first Inspector General of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), from 1922 to 1945.

The RUC was founded in 1922, following what became known as the Belfast pogroms of 1920-22, when Catholic streets were attacked and burned. It was conceived not as a regular police body, but as a counter-insurgency one. The new force contained murder gangs headed by men like a head constable who used bayonets on his victims because it prolonged their agonies.

It is the narrative of empire and of course, they applied it to Greece. That same combination of concentration camps, putting the murder gangs in uniform, and calling it the police. That is how colonialism works. They will use whatever means are necessary, one of which is terror and collusion with terrorists, and of course it delivers.

The head of MI5 reported in 1940 that “in the personality and experience of Sir Charles Wickham, the fighting services have at their elbow a most valuable friend and counsellor”. When the intelligence services needed to integrate the Greek Security Battalions – the Third Reich’s ‘Special Constabulary’ – into a new police force, they used him.

We must demonstrate the timelessness of such methods and the genealogy of legalising the fascist elements that are in the service of imperialism, offering them equipment, clothing and safe transport. The security battalions were supposed to be condemned by the exiled government in the Middle East if they continued to carry weapons after the withdrawal of the Germans. The same was decided in Tehran for all the collaborators of the Axis. The British tried to save the collaborators of the Germans cornered by the resistance, who were charged with horrific crimes against their compatriots throughout the occupation. They were taken to prisons like Goudi, gathering the outcry of the people who demanded justice.

Before the events of December, the people would see on the streets their former torturers moving around freely in a provocative way, ending up in the National Guard and becoming the guarantors of the monarcho-fascist restoration. We can only think of the recent coordinated efforts of the NATO countries for the evacuation of the ‘heroic’ fighters of Azov from Mariupol, in which Greece together with France and Turkey wanted to save the trapped fascists, or even the sporadic transfers of islamofascists from Syria and Iraq by US helicopters to other fronts of their dirty wars.

British imperialism shaped the character of the post-war regime in Greece and equipped it with the colonial methods that it had perfected in its historical course, such as the organisation of concentration camps and ways of torturing democratic and patriotic people, as first manifested in the desert of El Daba and then in the Greek prison islands of Gyaros, Makronissos, Agios Efstratios and other hellish prisons around the country.

History has nested in those prisons and places of execution, and the splendour of the Greek communists who defied death and torture spread its wings, not in words but in deeds, because they struggled for liberation, independence and integrity against fascism and for a better world without exploitation. As Communists of today, it is our duty to honour their memory and responsibility to learn from the history of their sacrifices. Where the Greek revolution failed other revolutions (like the Chinese revolution) prevailed. Every time the red flag falls in one place, it gets raised again in another and will continue to be raised until the final defeat of imperialism and the victory of socialism.