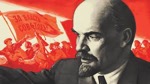

What is to be done

What is to be done? – presentation by Ella Rule of Lenin’s pamphlet to a CPGB-ML study school on 27 October 2022

The main thrust of Lenin’s pamphlet What is to be Done? is to define in broad terms how revolutionaries should do their work if they want to succeed in mobilising the masses of the people for proletarian revolution. Most of the pamphlet is devoted to lambasting the variety of opportunism he called ‘Economism’, and contrasting the type of work that revolutionaries should be doing as opposed to what this type of opportunist considers appropriate. He then goes on to explain how important a national newspaper is both for imparting information, raising class consciousness among the workers and helping to forge a centralised revolutionary organisation that would give maximum impact to the revolutionary propaganda by ensuring its distribution on a national level, not merely various local levels.

Revolutions are made by the oppressed masses, not by leadership organisations isolated from the people. Obviously the masses to such a huge extent outnumber the exploiters that the latter would stand no chance at all if the masses turned on them. What prevents the working class from doing so? Fundamentally it is a lack of understanding of what needs to be done and of the fact that together they have the means to do it. The first job that must be tackled is disseminating the necessary understanding, while at the same time building up a strong and efficient mechanism for organising the revolution when the masses are ready, i.e., the Party.

This is not an easy job at all. It requires all party cadres to acquire high levels of political understanding themselves in order to be able to spread that understanding as widely as possible to others. Indeed, it is in the course of working to spread the understanding to others that one is able to identify gaps in one’s own understanding which we then strive to close so that we are in future able to answer workers’ questions and respond correctly to their doubts.

In pre-revolutionary Russia, it would be hard to convince workers because of the prevalence of religious belief that persuaded people that they must accept their fate. Religion is not such a problem for us, but bourgeois ideology is blasted through to workers via radio and television – which Lenin didn’t have to contend with – as well as through the education system, and through the overwhelming weight of opportunism operating in the working-class movement, principally, but not exclusively, through the Labour Party.

In Lenin’s day the work of revolutionaries was hampered by the overtly repressive nature of the state, which was forever intervening to put the revolutionaries out of action, whether by imprisonment or murder. For the moment that is not a major problem in this country but just as much damage is done by the widespread illusions in bourgeois parliamentarism and bourgeois elections, which lead people to believe that if only they could get an honest person elected to parliament (or even the local council), he or she would be in a position to put everything right, or at least implement meaningful reforms.

However, regardless of the different nature of obstacles in the way of effective revolutionary work, the basic task of revolutionaries is the same and that is to diffuse revolutionary ideology among the working class and other oppressed masses.

The first point to be noted is that it is necessary to take revolutionary ideology to the working class because the working class is not able to generate that understanding spontaneously.

As Lenin points out (using the term ‘social democracy in the sense it had at the time of ‘revolutionary Marxism’, rather than the modern sense of ‘class collaborationism’):

“We have said that there could not have been Social-Democratic consciousness among the workers. It would have to be brought to them from without. The history of all countries shows that the working class, exclusively by its own effort, is able to develop only trade union consciousness, i.e., the conviction that it is necessary to combine in unions, fight the employers, and strive to compel the government to pass necessary labour legislation, etc. The theory of socialism, however, grew out of the philosophic, historical, and economic theories elaborated by educated representatives of the propertied classes, by intellectuals. By their social status the founders of modern scientific socialism, Marx and Engels, themselves belonged to the bourgeois intelligentsia. In the very same way, in Russia, the theoretical doctrine of Social-Democracy arose altogether independently of the spontaneous growth of the working-class movement; it arose as a natural and inevitable outcome of the development of thought among the revolutionary socialist intelligentsia”.

The Marxist understanding of the movement of history, the nature of capitalism, the nature of the socialism that must replaces it, etc., arise from deep scientific understanding that can no more be generated spontaneously by the masses than physics or chemistry. The masses are of course perfectly capable of understanding these things should they need to and put their mind to it, but it is necessary for a teacher to bring that knowledge to them.

The revolutionary worker goes among the masses precisely at those times when the masses begin to understand spontaneously that the system is not working for them and they are therefore looking for solutions. However, not all workers reach that spontaneous understanding at the same time. There will be some ‘advanced workers’ who start looking for solutions much sooner than others, and it is our endeavour to attract these advanced workers to our communist party to train them as revolutionaries in as great a number as possible so that when, as a result of deteriorating living standards and/or involvement in unjust wars, broader sections of the working class begin to look for solutions we have a large and well trained enough organisation to be able to meet their needs both for knowledge and for revolutionary organisation.

The biggest obstacle facing us is the fact that social-democratic prejudice is deeply embedded in the working-class movement. This is because its ruling class, being from an imperialist country, have been able, with the wealth they have hijacked from oppressed countries, judiciously to buy social peace by providing a middle class standard of life to working-class leaders and offering certain benefits to the broad masses of the people such as free healthcare and education, pensions and dole money – not generously but sufficiently to head off the level of popular discontent that would trigger riots. At the same time, workers’ unions, heavily linked to the Labour Party, have over the years often been able successfully to fight for slightly better pay and/or working conditions that the ruling class has only conceded, albeit reluctantly, because its imperialist interests enable it to do so without bankrupting itself.

Although the illusions in social-democracy are rapidly fading as the Labour Party remoulds itself more and more in the image of the Tories in order to reassure the ruling class that capitalism is safe in their hands, nevertheless the illusions in parliamentarism are still widespread.

The unions which had become very passive at the behest of their Labour Party bosses are at last becoming more active in organising working-class resistance in the face of the abrupt decline in living standards that has hit the working masses because of capitalist economic crisis aggravated by the costs of war. And the situation is going to get much worse. It is to be expected in the circumstances that workers who had previously seen no point in joining the union, leading to massive declines in membership, will now join and take part in the resistance taking place. In doing so such workers become ‘advanced workers’ – workers actively looking for a solution to the problems faced by their class. In other words, the pool of people who can be expected to be receptive to communist ideas is starting to increase. It is up to us to bring the understanding that trade unionism just isn’t enough and to try to recruit them to become revolutionaries. We will be strenuously opposed in this endeavour by most of the trade-union leadership which will devote itself to keep its movement within the bounds of capitalism.

In response to this situation, there are two main views as to how revolutionaries should proceed. The opportunist view is that all revolutionaries have to do is to join the working-class struggles and jolly them along, perhaps producing encouraging leaflets, joining picket lines, and perhaps arranging sandwiches for striking workers. Become their friends. Get them to trust you. Don’t present them with revolutionary ideas because that might put them off, there’ll be time enough for that once you have gained their trust. This is a message very much acceptable to the class-collaborationist trade-union bosses.

Lenin characterised this view as the ‘worship of spontaneity’, and was moved to point out that:

“…all worship of the spontaneity of the working class movement, all belittling of the role of ‘the conscious element’, of the role of Social-Democracy, means, quite independently of whether he who belittles that role desires it or not, a strengthening of the influence of bourgeois ideology upon the workers. All those who talk about ‘overrating the importance of ideology’, about exaggerating the role of the conscious element, etc., imagine that the labour movement pure and simple can elaborate, and will elaborate, an independent ideology for itself … But this is a profound mistake.”

The revolutionary view is that you join picket lines primarily to introduce revolutionary politics to the people who need them. It is not so much YOU these people need as the ideology that you bring with you. The last thing you should do is try to hide it, or postpone talking about it to some indefinite future date.

What you are bringing to the picket line, or to any other gathering of workers looking for solutions, is of course ‘theory’. And as Lenin never tired of saying, ‘without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement’. It is of necessity ‘theory’ because it is not present practice. The present practice cannot produce good results, therefore a theory needs to be introduced as to how present practice needs to be changed. One needs know nothing about how a car works as long as one can drive it – but what happens when it breaks down? This is when a theory is necessary on what should be done to repair it. And of course only a scientific theory – from someone who is familiar with how a car works – will be of any use. In the same way, in our broken-down capitalist society, theory is needed to find the way out – but not any theory put forward by any opinionated ignoramus but a scientific theory based on deep knowledge of the laws of development of human society as developed by Marx and his followers.

It therefore behoves all members of a revolutionary party to make every effort to master scientific socialist theory. This is a pretty tall order – it means learning philosophy, economics, world history, sociology as well as politics, and applying one’s learning to the changing realities of the world we live in and the class struggle, while all the time striving to pass on one’s understanding to others.

“This demands redoubled efforts in every field of struggle and agitation. In particular, it will be the duty of the leaders to gain an ever clearer insight into all theoretical questions, to free themselves more and more from the influence of traditional phrases inherited from the old world outlook, and constantly to keep in mind that socialism, since it has become a science, demands that it be pursued as a science, i.e., that it be studied. The task will be to spread with increased zeal among the masses of the workers the ever more clarified understanding thus acquired, to knit together ever more firmly the organisation both of the party and of the trade unions….” (Engels, Peasant war in Germany).

However, the opportunists who think only ‘practical’ work, such as cheerleading striking workers or electioneering in bourgeois elections, has any value, regard work on questions of theory as not counting as work at all! These are people who, in Lenin’s words, “cannot pronounce the word ‘theoretician’ without a sneer, who describe their genuflections to common lack of training and backwardness as a ‘sense for the realities of life’, [and thereby] reveal in practice a failure to understand our most imperative practical tasks”. Well, we have all met people like that! While it is of course true that theoretical work that is not combined with the practical work of spreading understanding to the widest possible extent is useless, it is also the case that practical work devoid of revolutionary content is just as useless. As the well known psychologist Kurt Lewin once said: “There is nothing so practical as a good theory”.

A favourite trick of the opportunists who seek to suppress the expression of revolutionary Marxist ideology is to claim that their literature that limits itself to applauding the spontaneous resistance of the masses amounts to ‘agitation’, while what the revolutionaries are seeking to do is all ‘propaganda’ which consistently goes beyond what interests ordinary workers. Lenin was at pains to point out that this opportunist definition of agitation and propaganda respectively is totally false:

“…the propagandist, dealing with, say, the question of unemployment, must explain the capitalistic nature of crises, the cause of their inevitability in modern society, the necessity for the transformation of this society into a socialist society, etc. In a word, he must present ‘many ideas’, so many, indeed, that they will be understood as an integral whole only by a (comparatively) few persons. The agitator, however, speaking on the same subject, will take as an illustration a fact that is most glaring and most widely known to his audience, say, the death of an unemployed worker’s family from starvation, the growing impoverishment, etc., and, utilising this fact, known to all, will direct his efforts to presenting a single idea to the ‘masses’, e.g., the senselessness of the contradiction between the increase of wealth and the increase of poverty; he will strive to rouse discontent and indignation among the masses against this crying injustice, leaving a more complete explanation of this contradiction to the propagandist. Consequently, the propagandist operates chiefly by means of the printed word; the agitator by means of the spoken word”.

In contrast to this, the Economists against whom Lenin was writing in What is to be done? opposed “the tasks of political propaganda and political agitation because these ‘force into the background the task of presenting to the government concrete demands for legislative and administrative measures’ that ‘promise certain palpable results’ (or demands for social reforms)…”. Lenin would certainly never have objected to ‘propagandist’ leaflets being distributed among his agitator’s audience that explained the reasons for the senseless contradiction between the increase of wealth and the increase of poverty in more detail.

Much of the reluctance to talk theory to the masses, even the advanced workers, stems from an elitist belief that only a person who has received a high level of education is capable of understanding theory, and that relatively uneducated workers are too thick to understand such things. This is of course total nonsense. Less educated people can understand the most complex ideas if they feel that they need to and they put their mind to it. What is true is that highly-educated workers generally have more time and skills at their disposal that enable them to access advanced theory more easily. But this is all the more reason why they should put their skills to work to impart their understanding to those who do not have these advantages, in particular to advanced workers,. And they should not be surprised to find when they do so that ordinary workers are predisposed by their life experience to accept these theories for more easily than those whose lives have been more privileged.

In this context, Lenin portrays an imaginary speech in which a worker addresses intellectuals thus:

“The ‘economic struggle of the workers against the employers and the government’, about which you make as much fuss as if you had discovered a new America, is being waged in all parts of Russia, even the most remote, by the workers themselves who have heard about strikes, but who have heard almost nothing about socialism. The ‘activity’ you want to stimulate among us workers, by advancing concrete demands that promise palpable results, we are already displaying and in our everyday, limited trade union work we put forward these concrete demands, very often without any assistance whatever from the intellectuals. But such activity is not enough for us; we are not children to be fed on the thin gruel of ‘economic’ politics alone; we want to know everything that others know, we want to learn the details of all aspects of political life and to take part actively in every single political event. In order that we may do this, the intellectuals must talk to us less of what we already know and tell us more about what we do not yet know and what we can never learn from our factory and ‘economic’ experience, namely, political knowledge. You intellectuals can acquire this knowledge, and it is your duty to bring it to us in a hundred- and a thousand-fold greater measure than you have done up to now; and you must bring it to us, not only in the form of discussions, pamphlets, and articles (which very often – pardon our frankness – are rather dull), but precisely in the form of vivid exposures of what our government and our governing classes are doing at this very moment in all spheres of life…”

Another tendency of those who worship spontaneity is the desire to shun all issues that do not touch on the workers’ present situation. A war in a foreign country? Boring. Even a strike in a different part of the country? Boring – workers are only interested in what is local to them! Again a profound mistake in Lenin’s view:

“Social-Democracy leads the struggle of the working class, not only for better terms for the sale of labour-power, but for the abolition of the social system that compels the property-less to sell themselves to the rich. Social-Democracy represents the working class, not in its relation to a given group of employers alone, but in its relation to all classes of modern society and to the state as an organised political force. Hence, it follows that not only must Social-Democrats not confine themselves exclusively to the economic struggle, but that they must not allow the organisation of economic exposures to become the predominant part of their activities. We must take up actively the political education of the working class and the development of its political consciousness”.

And further:

“Let us take the type of Social-Democratic study circle that has become most widespread in the past few years and examine its work. It has ‘contacts with the workers’ and rests content with this, issuing leaflets in which abuses in the factories, the government’s partiality towards the capitalists, and the tyranny of the police are strongly condemned. At workers’ meetings the discussions never, or rarely ever, go beyond the limits of these subjects. Extremely rare are the lectures and discussions held on the history of the revolutionary movement, on questions of the government’s home and foreign policy, on questions of the economic evolution of Russia and of Europe, on the position of the various classes in modern society, etc. As to systematically acquiring and extending contact with other classes of society, no one even dreams of that. In fact, the ideal leader, as the majority of the members of such circles picture him, is something far more in the nature of a trade union secretary than a socialist political leader. For the secretary of any, say English, trade union always helps the workers to carry on the economic struggle, he helps them to expose factory abuses, explains the injustice of the laws and of measures that hamper the freedom to strike and to picket (i. e., to warn all and sundry that a strike is proceeding at a certain factory), explains the partiality of arbitration court judges who belong to the bourgeois classes, etc., etc. In a word, every trade union secretary conducts and helps to conduct ‘the economic struggle against the employers and the government’. It cannot be too strongly maintained that this is still not Social-Democracy, that the Social-Democrat’s ideal should not be the trade union secretary, but the tribune of the people, who is able to react to every manifestation of tyranny and oppression, no matter where it appears, no matter what stratum or class of the people it affects; who is able to generalise all these manifestations and produce a single picture of police violence and capitalist exploitation; who is able to take advantage of every event, however small, in order to set forth before all his socialist convictions and his democratic demands, in order to clarify for all and everyone the world-historic significance of the struggle for the emancipation of the proletariat”.

There are ‘revolutionaries’ who imagine that it is better in Britain today not to go banging on about the war in Ukraine and the imperialist preparations for all-out war against Russia and China. Surely if people think these things don’t affect them, it is our job to demonstrate to them that they do, and to get them thinking about what can be done to prevent imperialists from launching such a war if and when it should happen. The war in Ukraine has direct relevance for the cost of living crisis, which itself affects not only people in work but all members of the working class. How is it possible to want to minimise the question of war in our agitation amongst the masses?

Equally, Lenin emphasises that it is by no means only in industrial struggles that advanced workers are to be found. They are also to be found in broad organisations founded to promote progressive causes. Examples in this country might be Stop The War and Palestine Solidarity Campaign. These organisations, we know from practice, tend to be dominated by social-democrats (in the modern sense – class collaborationists), who try to ensure that the voice of revolutionary socialism is stifled within their organisation, on its platforms and in its publications, but nevertheless every effort should be made to address their followers in whatever ways may be open to us. Another venue has been the Workers’ Party of Britain that attracted those people whose illusions in social-democracy and in some cases parliamentarism had been shattered by the downfall of Jeremy Corbyn. Here we entered into alliance with progressive non-communists who sought to organise such people to create a party that would give voice to the interests of the working class now that it was clear that the Labour Party would certainly never do it. Was it wrong, was it opportunist, of us to form such an alliance?

Lenin’s answer would certainly have been Not at all!

On the contrary, “the representatives of the latter trend [the ‘legal Marxists’, i.e., non-revolutionary Marxists] are natural and desirable allies of Social-Democracy insofar as its democratic tasks, brought to the fore by the prevailing situation in Russia, are concerned. But an essential condition for such an alliance must be the full opportunity for the socialists to reveal to the working class that its interests are diametrically opposed to the interests of the bourgeoisie”.

Lenin warned that nevertheless such alliances will not necessarily last forever, as the non-revolutionary elements seek to suppress the expression of revolutionary Marxist ideology (often in the name of Marx!):

“However, the Bernsteinian and ‘critical’ trend, to which the majority of the legal Marxists turned, deprived the socialists of this opportunity and demoralised the socialist consciousness by vulgarising Marxism, by advocating the theory of the blunting of social contradictions, by declaring the idea of the social revolution and of the dictatorship of the proletariat to be absurd, by reducing the working-class movement and the class struggle to narrow trade-unionism and to a ‘realistic’ struggle for petty, gradual reforms. This was synonymous with bourgeois democracy’s denial of socialism’s right to independence and, consequently, of its right to existence; in practice it meant a striving to convert the nascent working-class movement into an appendage of the liberals.

“Naturally, under such circumstances the rupture was necessary”.

This observation of Lenin’s holds true for proletarian parties in all countries.

Lenin also dealt with the question of whether we should self-censor for the sake of unity. His answer was Certainly Not!

“We are marching in a compact group along a precipitous and difficult path, firmly holding each other by the hand. We are surrounded on all sides by enemies, and we have to advance almost constantly under their fire. We have combined, by a freely adopted decision, for the purpose of fighting the enemy, and not of retreating into the neighbouring marsh, the inhabitants of which, from the very outset, have reproached us with having separated ourselves into an exclusive group and with having chosen the path of struggle instead of the path of conciliation. And now some among us begin to cry out: Let us go into the marsh! And when we begin to shame them, they retort: What backward people you are! Are you not ashamed to deny us the liberty to invite you to take a better road! Oh, yes, gentlemen! You are free not only to invite us, but to go yourselves wherever you will, even into the marsh. In fact, we think that the marsh is your proper place, and we are prepared to render you every assistance to get there. Only let go of our hands, don’t clutch at us and don’t besmirch the grand word freedom, for we too are ‘free’ to go where we please, free to fight not only against the marsh, but also against those who are turning towards the marsh”. In fact, it is our revolutionary duty to do so.

The overwhelming majority in our Party who have refused to be dragged into the marsh of opportunism have been roundly condemned as destroying the party as a result of their dyed-in-the-wool antiquated ideas, just as Lenin himself was slandered by the opportunists in his day: “’Dogmatism, doctrinairism’, ‘ossification of the party – the inevitable retribution that follows the violent strait-lacing of thought’ – these are the enemies” against whom the opportunists like to claim they are fighting. It would seem that our Party is in good company!

There are a million exposures to be made about the iniquities that the capitalist system inflicts on the working class, and all of them need to be exploited for the purpose of raising the class consciousness of the workers to the point that they not only understand that capitalism must go but in addition are prepared to do what it takes to force it out.

One of the best vehicles for such exposures is the party newspaper, which needs to be made available all over the country. Lenin stressed the great importance of an all-Russia newspaper for the purpose of putting the whole picture of the rottenness of Tsarism before the Russian people. It was also a means of avoiding duplication of effort – something very important as the party was relatively small, as it was produced at a single centre so that the necessary research did not have to be done over and over again at different centres and expertise could be pooled to great effect.

Of course dissemination of the newspaper is an extremely important element of practical work, practical work that in our Party was seriously curtailed by the pandemic but which is now restarting in earnest. Of course we do have a presence on the internet and on social media – resources obviously not available to Lenin – but the advantage of the newspaper is that it demands real life contact with real people with whom discussions can be held, enabling the vendor to learn more about the concerns of ordinary workers while at the same time addressing those concerns and putting them into the context of the class struggle.

Notwithstanding the tremendous advances that have been made since Lenin’s day in the field and mode of communications, the importance of a single nationwide party newspaper cannot be exaggerated. Such a newspaper performs the role of a propagandist, an agitator and, to a certain extent, an organiser. A Party can only cast out of the window a central organ at its peril

Lenin is saying to us: get out there and sell your newspapers. Talk to people as you do so, make contacts among the masses. Encourage people to join your study classes and draw them closer to the Party. This highly practical work is appropriate at all times.